Where Classical Precision Meets Cultural Revolution on the Jubilee Stage

Review by Lauren Kalinowski

February 21, 2025

Jubilee Auditorium

Nyman String Quartet No. 2

Composer: Michael Nyman

Choreographer: Robert Garland

Take Me With You

Music: Radiohead

Choreographer: Robert Bondara

Pas de Dix (excerpt from the ballet Raymonda)

Composer: Alexander Glazunov

Choreographer: George Balanchine

Return

Music: James Brown, Alfred Ellis, Aretha Franklin, Carolyn Franklin

Choreographer: Robert Garland

The auditorium falls into reverent hush as the house lights dim, leaving only the soft glow of aisle markers illuminating expectant faces. Programs rustle then still in laps as dark trembles with subtle movement hinting at unseen dancers behind it.

The bold ballet explodes to life on stage with its first piece set to the staggeringly beautiful String Quartet No. 2 composed by minimalist Michael Nyman. It unleashes a revolutionary vision that transforms what we understand ballet to be.

Hip hop, jazz, and African dance groove seamlessly together as classically trained dancers blend diverse styles with technical precision. In this Alberta Ballet-hosted performance of Dance Theatre of Harlem at the Jubilee Auditorium on February 21, 2025, the music becomes as essential as the movement itself—a perfect symbiosis of sound and body.

I don’t often see shows with more men in performance than women. Here it is. We’re talking ratios of 5:1 men to women. Thicc, muscular thighs that might easily carry a quarterback are elegantly propelling jetes in quick allegro across the Jubilee stage.

The group of ten dancers are poised but loose in an intentional way, upper bodies genuinely having fun as they move with tight, quick footwork. I’m taken aback by the athleticism, and the pure joy obvious in their movement.

This is not ballet I’ve seen before in Alberta. It’s The Dance Theatre of Harlem’s (DTH) premier performance in the province, and we’re lucky to have had it at this exact moment in time.

As I watch the dancers seamlessly blend classical technique with contemporary expression, I’m witnessing the living embodiment of DTH’s revolutionary mission. Founded in 1969 by Arthur Mitchell, the first Black principal dancer at New York City Ballet, in the aftermath of Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination, this company doesn’t just perform ballet; it reimagines it. “Mitchell was the first black principal dancer of a major ballet company at New York City Ballet,” Robert Garland, the Artistic Director tells me.

The set has a simple backdrop: three spotlights with varying pink to blue light creating silhouettes and playing with shadow. A male soloist, Derek Brockington, is elegant, effortless, and parades his personality. The movement contrasts with rhythmic music on classical stringed instruments, evoking the distinctive compositions of Michael Nyman, the wonderful contemporary composer celebrated for his evocative film score for The Piano, as aptly described by Garland.

At times the corps was out of sync with each other and each added their own individual flair. They showed they could perform balletically with technical precision, but mixed it up with other styles of dance. The costumes, simple empire waist tennis style dresses for the ladies and singlets for the men, in light pinks and blues, left the focus on their bodies.

The dancers marched on and off stage with flexed feet, the antithesis of ballerina runs, but then flipped back to tight pas de chats and beating sautees, then switched again to hip hop posture on ballet feet. They were code switching in movement, playing with the audience. Intentional flat feet and parallel knees made me cringe for a second, but it was quickly soothed away with elegant arabesques and gentle port du bras. When the dancers code-switch between balletic precision and hip-hop posture, they’re not merely changing styles, they’re continuing Mitchell’s work of expanding who belongs on the ballet stage.

This is what we need to move ballet forward.

The show was choreographed “with a little bit of something for everyone, it’s very important to me that, because there are some people not coming to ballet any longer, you know or never heard of classical music,” says Garland, and this gives them a sampling of everything in the ballet world today.

The lights came up at the conclusion of the first Nyman piece, with a twenty-minute intermission. It felt abrupt and quick; classical ballet viewers are generally accustomed to a performance in one or two acts, with longer periods of sitting near 40-50 minutes at a time. It wasn’t unwelcome though, standing in the lobby during the first intermission watching fashion go by. It’s just as enthralling a performance as the show itself.

A couple in matching sequin pinstripe suit jackets and tuxedo pants, complete with patent Oxfords, joked with each other. A tall woman in a head to toe bubblegum pink embroidered Asian silk pantsuit with spike heels strutted by. Pops of personality across the rainbow floated through the crowd in colourful high heels in all shades and styles, and there was blue hair, teal hair, pink hair and coiffed hair throughout.

Of course, we had a good share of character glasses. A beehive hairstyle stood tall above the sea of people. The ballet brings such beautiful artistic diversity within Edmonton together. I admired a neon green mock-neck turtleneck under a simple sports jacket, a tiny woman’s palm-sized West Coast indigenous whale broach in hammered silver and another’s tall burgundy velvet stilettos with rosettes on the toes. Rarely do we see such displays of fashion in our winter city.

The middle act of the show commenced with Take Me With You, set to Radiohead’s hypnotic “Reckoner,” its shimmering percussion and Thom Yorke’s ethereal falsetto creating a dreamlike atmosphere that perfectly framed the dancers’ undulating movements. Robert Bondara’s choreography opens to a black unlit stage. I’m taken to what feels like dancer Lindsey Donnell’s personal moment, she’s dressed in a white collared shirt knotted at the waist and black shorts She’s clapping a rhythm as she walks. Lost in a moment, perhaps visualizing the choreography, feeling the music.

Donnell is joined by magnetic partner Elias Re, also tapping, immersed in the rhythm for a contemporary lyrical duet as the percussion of the music track comes in.

Flowing together in a powerful on stage presence, the duo is light, smooth and acrobatic. Her lines are perfect, his masterful hold on her feels organic and intuitive, they move in sync, fluid like water ripples. I’m carried with them on sea of a musical current. And then it’s over too quickly.

With a brief five minute pause, the lights are up again but we stay in our seats. This is a mixed repertory performance of several small pieces, and the format is typical though each piece is usually longer. It keeps the audience awake and engaged.

The benefit of this style of show, a survey of various dance forms and music choices, is to show a number of disconnected mini-ballets without a story. Garland structures the performance in the Balanchine tradition of abstract ballet, where movement exists for its own sake rather than to tell a story. There’s no miming of action to tell us what’s going on or over the top set. The audience is privy to personal expression and intimate moments of dance, as clear in stand-alone number Take Me With You, I feel lucky to witness the personal experience of dancing.

As I wait for Pas de Dix, I notice the stale-peanut smell is coming from my program booklet. What kind of press was used for the printing? It’s been distracting me through the evening and now that I’ve identified the source I’m weirded out.

With no idea of what to expect next, the audience gives an audible “oooh” as the curtain rises to tutus, tiaras and traditional tights.

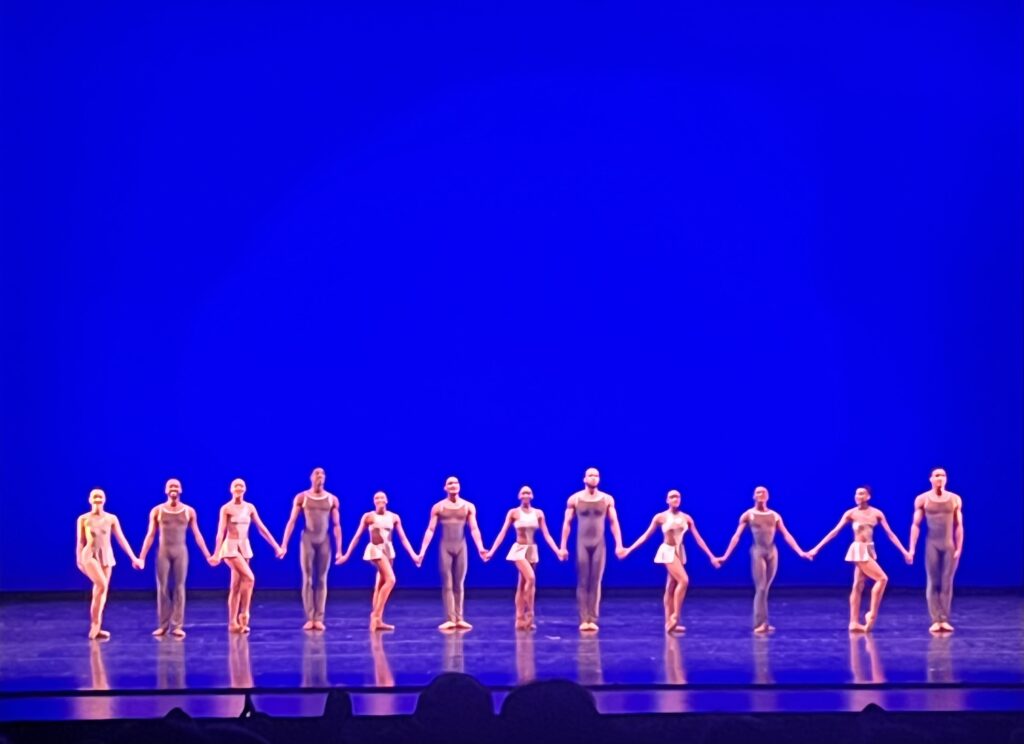

As indicated in the title Pas de Dix, en francais, we have ten dancers, five couples, and they’re dancing to Glazunov. This is the piece that highlights Dance Theatre of Harlem’s dancers outside the ballet norm.

They show us they can dance classically, the technique, skill and grace are there. This is the least enjoyable piece of the show, it’s there as though to say, “look, we are professional ballerinas and we have the ability to do this.” They all have strong lines, they know their bodies, but the corps doesn’t always match each other. Perfection and unity should be the emphasis in a piece like this, and it’s here we see the individuals over the group.

Traditionally, ballet companies will often choose dancers with their heights in mind for uniformity, and there are only a couple inches between the tallest and shortest. The eye is drawn to what stands out: mismatched tights, skirts that hang at different heights, even the angle of the wrists in a slow arm movement. We are trained to make everything match.

Fellow dancers I’ve known have had to change their hair colour and cover tattoos blend in with each other. We don’t want the eye to follow “imperfections” or what stands out, we want it to be the same. There’s a reason dance mistresses demand the exact shade match in red lipstick: the audience will immediately see the difference.

I’m bothered by my reaction but I understand it’s from years of conditioning to create uniformity. Dance Theatre of Harlem is here to show us another way to ballet, a better way. But it takes a lot of breaking of expectation and tradition.

The boringness of this piece shows me how successful the company is in doing what they do best. Hundred year old performances do need to be reinvented for the art to move forward, but we can pay homage to the classics. It’s like the saying we need to know the rules to break the rules; Picasso had to study the Renaissance masters so he could create Cubism.

DTH and all ballet companies, to be what they are, need to master the tradition and then they show us they can break from it so well while maintaining the integrity of the dance.

Fussy, old fashioned me thinks “there is too much going on with the arms, the hands aren’t in life” and at times the timing of movement of the dancers is slightly off from each other. They have tidy feet, amazing control of turnout and flexibility, and it’s accidentally predictable when we hear a timpani cue a male grand allegro sequence. The tempo, rhythm and percussion signal this, we might recognize it from The Nutcracker at the start of the grand allegro before the principal solo.

In fact, the Pas De Dix should be recognized as quite similar in style to The Nutcracker, both are Eastern European folksy ballet styles. The big jumping, exaggerated footwork and up and down movement with full gestures; the deep squats that prepare for incredibly high jumps of a fast tempoed trepak. These are not dainty men on stage. They’re exemplifying how meticulous ballet needs to be, traditionally, and I’m feeling as a viewer that the classical is predictable.

They’re wearing shades of pumpkin orange bodices that contrast with the dull blue backlit screen. The traditional ballet hierarchy speaks through the costumes, the stars in white tops versus the corps in orange. Personality becomes muted. The crowd certainly reacted to this third piece, but I can say we could have done without it. I suppose it checks the box.

At the second intermission I overheard someone say “the dancers are no different than the regular company” that we’re used to here in Edmonton. And after that third piece, I can see where he’s coming from. But that piece also showed me exactly how ballet can evolve.

“DTH wears flesh coloured tights and ballet shoes – the colour of our legs matches the colour of our face…so when you’re looking at the stage you see all different colours of skin tones united in movement, it celebrates diversity”, says Virginia Johnson, past Artistic Director of DTH in a 2018 interview. And that stood out on stage here.

It’s unusual to see a full ballet company of mostly brown bodies. Like an x-ray reverse image, the group of the dancers is all dark but with one light skinned dancer, versus our traditional all white with perhaps one darker skinned dancer. I’m highlighting this because it’s important. It’s what DTH is built upon. Johnson says, “we’re using ballet to make people think again about so many different parts of their lives” and politically it’s making a statement about thoughts on who should be on stage.

There’s no shortage of dancers expressing that racism and colour discrimination is part of the art. Search Robert Garland, Misty Copeland, or Raven Wilkinson for discussion of the topic. The founding of this ballet school changed the definition of what ballet can look like today.

At the beginning of DTH’s formation, it was more than a ballet company. Garland explains, “when the first artistic director of NY City Ballet, George Balanchine came to America, he said, ‘first I have to have a school.’ And DTH cofounder Arthur Mitchell lived by that as well. You know, first the school and within a couple months, he had hundreds of kids that proved the critics were wrong that his community would not be interested in ballet, because they most certainly were.”

That community being black dancers and dancers of colour.

Ruby Bridges, the first little African American child to attend a formerly-whites only school in New Orleans faced incredible protest and outrage in 1960, right around the same time DTH was formed. Ruby Bridges is only 70 years old this year. That means that Black principal dancers were unusual, outside the norm and often unwelcome within the lifetime of many people alive still today. As Return begins with silhouettes against a red backdrop, I’m reminded that only within my lifetime have Black principal dancers become accepted in major ballet companies. The silent silhouettes on the stage represent voices that were systematically excluded from this art form for generations.

And with the recent DEI orders and funding cuts, America seems to want to go backwards to take away spaces like Dance Theatre of Harlem where little black kids can see dancers that look like them taking professional ballerina roles and giving representation. Artistic spaces where freedom of expression thrive are being threatened (as in the Kennedy Centre takeover), and it’s going to eliminate people from all sorts of other places. And that’s wrong. Because all humans need to have a place to exist and express themselves. I wonder what the man who said “the dancers are no different than the regular company” was seeing.

The third act, the one we all came for, the well known Return, set to Aretha Franklin and James Brown, was the highlight of the show. They saved the best for last.

It starts in silence, with two dancers, male and female, silhouetted against a red background. It’s so quiet I can hear their shoes squeak with their turns. This performance is about their bodies and lines and the movement, colour is irrelevant. As the music comes up I’m watching a jazzy number in flirty skirts, hips swinging and the dancers doing what they do best. Oh, but ballerinas aren’t supposed to have hips, let alone use them.

Baby, baby, baby, Aretha croons, as the striking Kouadio Davis manipulates his partner, Lindsey Donnel like she’s a Barbie doll with hips that spin 360 degrees. Lights blink at different points in the piece like photography flashes at a fashion show, and we’re sitting at a catwalk with ballerinas strutting on and off the stage. When Davis and Donnel move to Aretha Franklin’s soulful voice, they’re not just dancing; they’re reclaiming space.

The mini ballet transports the audience, it’s a callback to 90s fashion sensibility and 1960s soul. The fundamentals of ballet are still there, but it’s sensual, acrobatic, jazzy and swaggy. Imagine Swan Lake flat footed cygnet hops to James Brown’s funky rhythms.

Again, the ending left me wanting more. I wanted a proper finale with a grand resolution. All the dancers came together on stage but the piece ended without the customary triumphant conclusion. Perhaps this, too, is intentional: a statement that DTH’s revolution of ballet is still ongoing, still evolving, and far from finished.