Edmonton Opera starts its pocket-sized Ring Cycle

Review by Mark Morris

Photos by Nanc Price

Wagner: Das Rheingold

adapted by Jonathan Dove and Graham Vick

Stage Director: Peter Hinton

Set, lighting, and projection designer: Andy Moro

Costumer designer: Brianne Kolybaba

Neil Craighead ……………………….Wotan

Roger Honeywell ……………………Loge

Dion Mazerolle ……………………..Alberich

Catherine Daniel …………………..Fricka

Sydney Frodsham ………………….Erda

Jin Yu………………………………………Donner

Vartan Gabrielian……………………Fasolt

Giles Tomkins…………………………Fafner

Jaclyn Grossman…………………….Freia

Mariya Krywaniuk …………………Woglinde

Madison Montambault………….Welgunde

Renee Fajardo……………………….Flosshilde

members of the Edmonton Symphony Orchestra

Conducted by Simon Rivard

Maclab Theatre, Edmonton

May 29, 2024

2024/2-25 is a bumper season for Wagner’s epic Ring cycle. Thielemann is conducting a new production in Milan, Jurowski in Munich, Heras-Casado in Paris, and Covent Garden will continue its cycle with Pappano conducting Die Walküre. Zurich has already streamed an interesting new cycle in May (available free until June 15 here).

In North America, Dallas Opera are putting on a semi-staged Ring in October, and here in Alberta we have seen Calgary Opera’s production of Rheingold (review here – alas, there are no plans to do the whole cycle), and now Edmonton Opera have ended their current season with Rheingold, the first opera in their cycle. Die Walküre is scheduled for 2025.

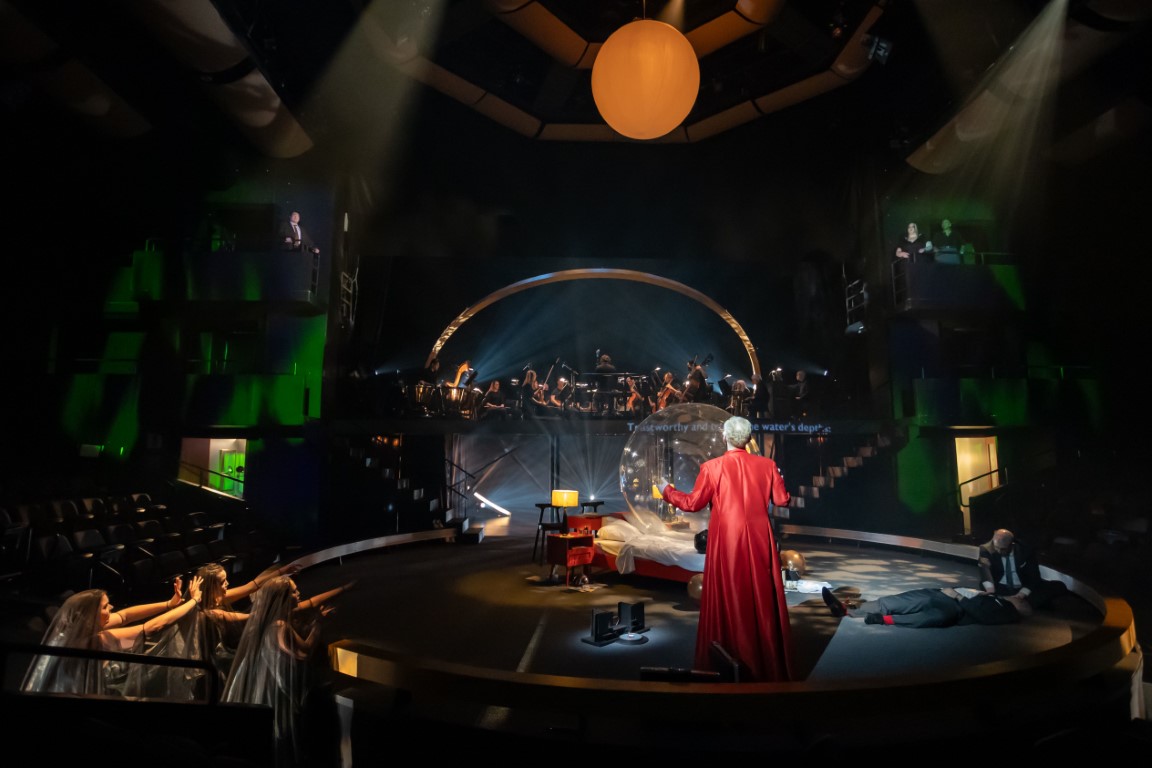

Calgary Opera chose a generally conventional production, originating with Minnesota Opera, with a reduced orchestra to fit the Jubilee South stage. Edmonton Opera’s solution to budget and size restraints is much more radical. The scenario is reduced to one setting, on the thrust stage of the Maclab Theatre in the Citadel complex, a much smaller venue, with the audience ranged on three sides.

The orchestra consisted of just 18 players drawn from the Edmonton Symphony Orchestra, along with Jeremy Spurgeon providing more depth of sound on the organ. This compares with the over 120 players Wagner’s score specifies, and 54 in the reduced Universal edition often used for smaller venues. They were placed on a tier above the back of the thrust stage.

All this is billed in the program as originating in the Birmingham Opera Company’s production, using a concept by Jonathan Dove and Graham Vick, who died of Covid just before he was due to direct it (the original Dove concept was premiered by the City of Birmingham Touring Company in 1990). It is difficult to see, though, what exactly came from Birmingham, as their 2021 production included Mime (absent here), had an orchestra of 87, and Wotan – ‘our leader’ – gave a news conference to announce his ‘Your Lives Matter’ campaign to kick off the production.

The quite considerable cuts, whether originating in Birmingham or Edmonton, reduced an opera that usually takes around 2 hours 20 minutes without intermission to 1 hour 50 minutes. Edmonton Opera did have an intermission, against Wagner’s wishes, and they had it in just about the worst possible place: just after the (canned) anvils had started as Wotan and Mime arrive in Alberich’s mines. The German text, on the other hand, is all Wagner’s, and there is no attempt to put in topical local comments. The music, insomuch as it can be with such reduced forces, remains faithful to the original.

The actual staging is a bed placed in the middle of the stage. The invented conceit is that this is a hotel room in Edmonton – the entrance door and the room’s bathroom flank the back of the thrust stage – and the opera opens with Wotan asleep on the bed, dreaming the whole thing, German Rheinmaidens and all.

What to make of such a pocket Rheingold? The first thing to say it that it was theatrically more engrossing than I was expecting, and consequently more entertaining. The second is that, while it represented Wagner better than EO’s Don Giovanni represented Mozart and da Ponte, I do hope that those unfamiliar with the opera, didn’t go away thinking that is what Wagner’s opera is like. It isn’t.

Such cut-down versions have their place – I vividly remember the first I ever saw, a production of Marschner’s Der Vampyr at the Vale of Glamorgan Festival in the 1980s, originating from a fringe company in Stuttgart. That, though, was of an opera I was unlikely otherwise to see (and it took me 30 years to find a recording of the whole opera). But I think the concept has validity for those cities that do not have an opera company financially and artistically capable of staging the full thing.

The director Peter Hinton-Davis, in his program note, states it was “created in a spirit of making it not smaller, but rather, more far reaching and accessible to new audiences”. This seems to me ingenuous, implying that new audiences aren’t capable of appreciating a full Ring. Wagner would have hated having his operas messed around with for such a purpose, which strikes me as a kind of appropriation. If that was the intent, much better not to do it at all.

Such a justification, though, simply wasn’t needed for this production. In terms of presenting the core of the drama and the music in a way that was viable for a company without those financial resources, it worked quite well – especially if seen as an introduction to Wagner for new audiences, who might then be encouraged to see the full thing.

What was lost in this production was any sense of magic, or rather that kind of human and spiritual depth that myth – and the Ring is the most mythical of operas – can evoke. This wasn’t the fault of the concept or the thrust stage, but rather of the choices made for the dramatic action. One can understand the failure to represent any kind of Valhalla at the end in a cut-down staging. However, the Rheinmaidens’ gold was virtually non-existent, represented by rather farcical large blown-up balloons, that became particularly silly when trying to cover Freia. Donner’s hammer was equally risible, an emaciated dollar-store item – surely he could have been given something closer to a sledgehammer. There was no real attempt to represent toad or dragon, and the hotel/dream metaphor simply wasn’t needed – the staging could have worked perfectly well without it.

Nor was it either logical – or necessary – to designate the hotel location in Edmonton. There is something really hokey about doing this (EO did the same thing in Don Giovanni), and it suggests that the company views Edmonton audiences as so unsophisticated that they have to be given such a parochial sop.

Against all of that, this Rheingold had the kind of dramatic flow and tension that one associates more with the theatre than with opera, partly created by a very different relation of audience to action that a thrust stage requires. Having three sets of surtitles, so that all the audience could read them, helped.

It also had some particularly fine performances. Dion Mazerolle, suitably dressed as a miner, was both dramatically and vocally an outstanding Alberich, forceful as much as cunning, with an underlying sense of class tension. The highlight of the evening was his reaction to the loss of the Ring and his subsequent curse. Catherine Daniel’s portrayal of Fricka, Wotan’s wife, was full of insight, and powerfully sung – she was vocally much more comfortable in this role than she had been as Erda in Calgary. So often Fricka is portrayed as an demanding but ineffectual woman, but here there was also a genuine tenderness in her interaction with her husband. I do hope she gets the chance to sing the role with a mainstage opera company.

I personally did not like Roger Honeywell’s portrayal of Loge, but I appreciated his consistency and commitment to his interpretation. The music suggests someone far more flighty and trickster-ish than the wise old man figure Honeywell created. Both vocally and dramatically he was perhaps miscast. Neil Craighead was a strong Wotan vocally, but dramatically stolid, not achieving the sense of driving desire for power that the part requires. The giants, Vartan Gabrielian as Fasolt and Giles Tomkins as Fafner, appeared as slightly shady business lawyers, and were far more effective than their Calgary counterparts, Tomkins especially convincing vocally. The Rheinmaidens were a mixed trio, with Mariya Krywaniuk rather out-of-place vocally and dramatically. Sydney Frodsham brought an otherwise absent sense of solemnity to the proceedings as Erda. Quite why Freia (Jacklyn Grossman) was costumed to look like a Goth matron who had come in from a rain-storm, black make-up streaming down her face, was beyond me.

Things were not so happy in the orchestral tier. From what I have heard of Simon Rivard’s conducting, there is little individuality or nuance, seemingly concentrating on accompanying singers rather than creating his own imprint. This performance was no exception. The members of the Edmonton Symphony were not at their best either, in spite of some bright individual moments, with too much ragged playing and too little sense of being one of the main protagonists of the opera. The dancing fire music at Loge’s first entry was simply awful. If you are going to do an arrangement with so few players, then they and the conductor have to be really spot on, and they weren’t here.

It was good, though, to see that both Calgary and Edmonton have had packed performances for Wagner’s opera, which had never been performed in Alberta before – though Calgary showed that they could fill a much larger capacity Jubilee while still presenting a fairly traditional production.

Traditional productions, however, now seem to be a thing of the past with Edmonton Opera. Their 2024/25 season, recently announced, has little traditional or conventional about it. The only Jubilee production (and the only one with the ESO) is of Strauss’ Fledermaus – EO last presented it in their 50th season in 2014, in what was a sparkling event. Ten years later, their production will reimagine the operetta to portray “a local community theatre company coming together to perform their own rendition of Die Fledermaus“. Bartók’s magnificent, dark, two-handed opera Bluebeard’s Castle (opera lovers will remember Robert LePage’s spellbinding production that Edmonton Opera presented in 2006), an opera where the orchestration is paramount, is being converted into a love story built around dementia and looking back into the happy past, with an orchestra of seven players and a new English text.

Then there is the second opera in the Ring cycle, Die Walküre, which I am looking forward to, first to hear some of the Rheingold singers again, and then out of curiosity at how the concept of the Ring cycle is continued, in what is my favourite opera.

One thing has to be said. These reimaginings of opera that Joel Ivany is bringing to Edmonton, these hybrids his company is presenting, have their origins in cities where audiences have the opportunity to see unadulterated opera – be it in Toronto (where he is the artistic director of the Against the Grain company), Birmingham, UK (the city of origin of this Ring) or London, UK (the city of origin of the Bluebeard). In such places, when you know the original, such reimaginations can be fascinating and powerful. But they exist as a kind of experimental fringe, and that is their real value.

Edmontonians have experienced and enjoyed mainstream operas, along with the occasional experimentation, for 60 years, thanks to Edmonton Opera. That, judging by this season and by next season’s offerings, now seems to be less and less likely. Yes, we can admire what Joel Ivany is doing – though I would admire it much more if he expressed his ideas in new operas rather messing around with old ones. But there is a real danger than in doing what he is doing, he is, in fact, destroying mainstage opera in our city. That would be a pity, for then then the ability to experience what Wagner or Bartók or Mozart actually created, would be confined only to those rich enough to fly to the very many cities in the rest of the world where opera is honoured, and its compositions respected.

New information on the City of Birmingham Touring Company origins of Jonathan Dove’s arrangement of Das Rheingold was added to this review on February 4, 2025. Many thanks to the Music Librarian of the Opéra National de Lorraine for supplying the details.