“I have realized something that I have willfully ignored: I identify as Ukrainian, though I am of mixed European heritage, but I know nothing about this culture.”

By Kelsey Brick

Once again Easter has come and gone.

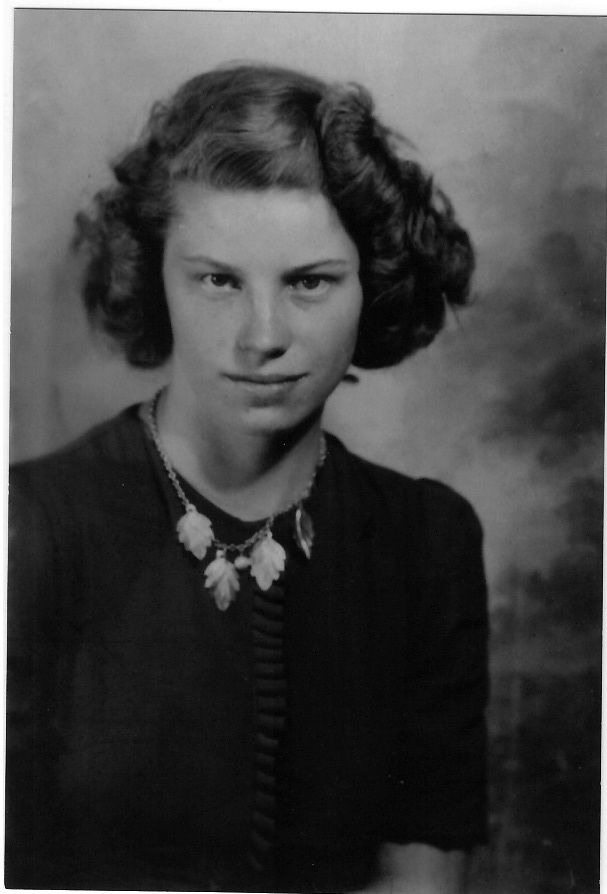

I don’t really celebrate this holiday, but I do have a family connection to the tradition of pysanky—Ukrainian Easter Eggs. My Grandma was Ukrainian, but neither my mom, nor my three aunts and two uncles know much about their mother’s past. She passed away in October 2003. I was 21 and still young when she died. Now, during most holidays I get an urge to learn more about my Ukrainian heritage.

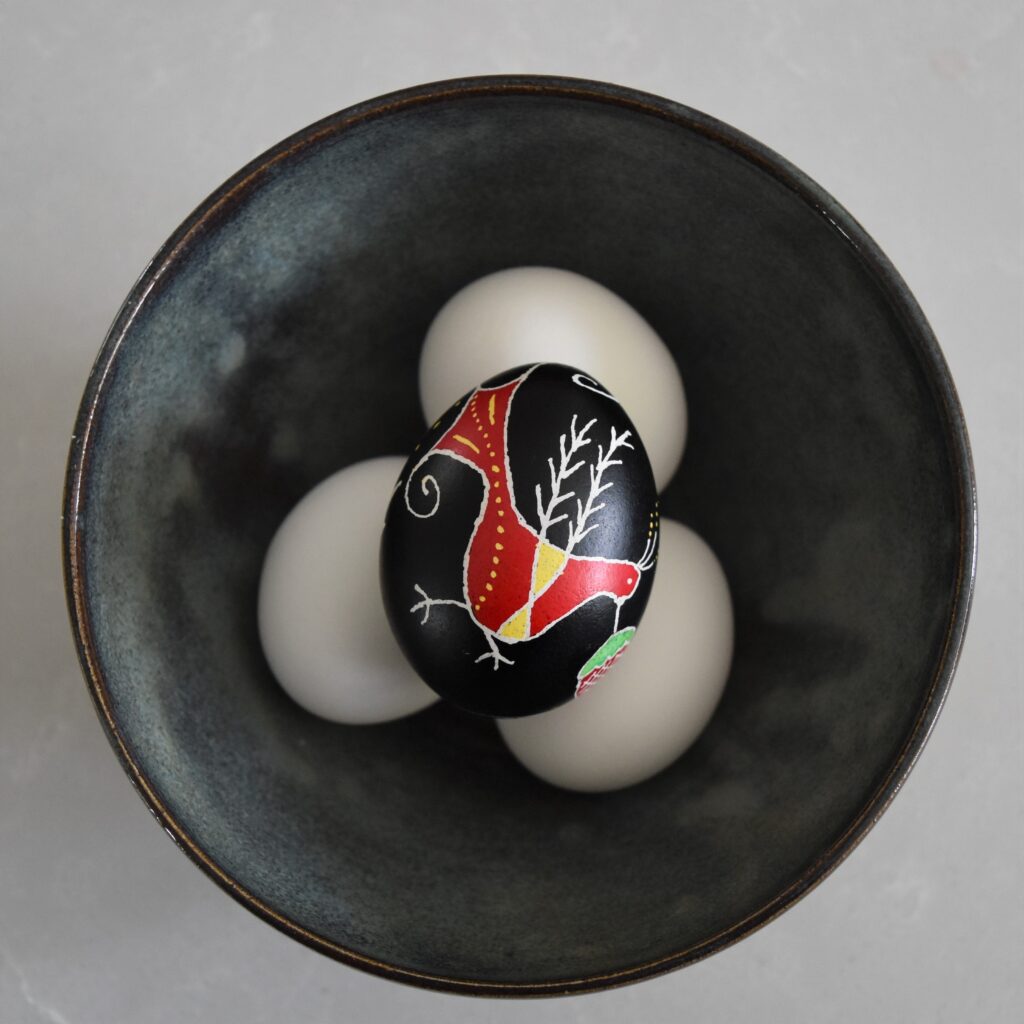

This year, I decided to give egg decorating a try. Pysanky are created through a wax-resist technique and dyes (similar to the cloth art of batik). For as long as I can remember, I have been carrying around the basic tools used for writing pysanky. I have this ratty plastic Ziploc bag with a kistka (the wax writing tool), beeswax, and metal poker (used to remove the innards of the egg). These tools once belonged to my Grandma.

My original plan was to pick a design from one of the library books I checked out and follow its instructions to create my egg. The process is pretty simple, but I soon discovered it is endlessly complex and full of symbols and meaning. The designs and colours are characteristic of specific regions and are often a combination of talismanic, Christian, folk, and ritual beliefs.

I do have vague memories of decorating pysanky with my Grandma. As I held the wooden handle of the kistka in my hand and examined its burnt metal tip, I was struck by the thought that pysanka is more of a feeling than an actual recollection. I reached out to my mom, aunts, and uncles to see what they remembered, and they all claimed that my Grandma was not really much of an egg decorator. The only thing they could recall was dipping boiled eggs into coloured dyes.

“But, don’t kid yourself,” my mom laughed. “These were eaten and the shells were tossed into the garden. There was no way your Grandma was going to waste good food when she had eight mouths to feed.”

The dying and eating of eggs at Easter is known as krashanka and it’s a common Ukrainian tradition. The book I checked out of the library taught me that—not my family. In fact, everything I learnt about the tradition of pysanky during this process I learnt from books. I never even knew the proper term for one before I started to write this piece. I learnt this from the same library book: Pysanky, or the singular pysanka, is an extension of the Ukrainian verb pysaty, meaning ‘to write’.

I have realized something that I have wilfully ignored: I identify as Ukrainian, though I am of mixed European heritage, but I know nothing about this culture. But, I also discovered that my Grandma was also disconnected from her roots:

“Your Grandma gave up on being Ukrainian a long time ago. We were the only kids on her side that could not speak the language. She always just said it was a stupid old language we didn’t need to know.”

So instead of following the design in the library book, I decided to create something that would honour my family’s history and the memories of my Grandma. Maybe this would help me shrink the distance between myself, my Grandma, and our Ukrainian culture.

I am not sure if I believe that my Grandma had rejected her Ukrainian heritage. It may seem this way on the surface, and I know that she was a stubborn lady who may have argued otherwise. The Ukrainian culture remained a ghostly shadow in her life.

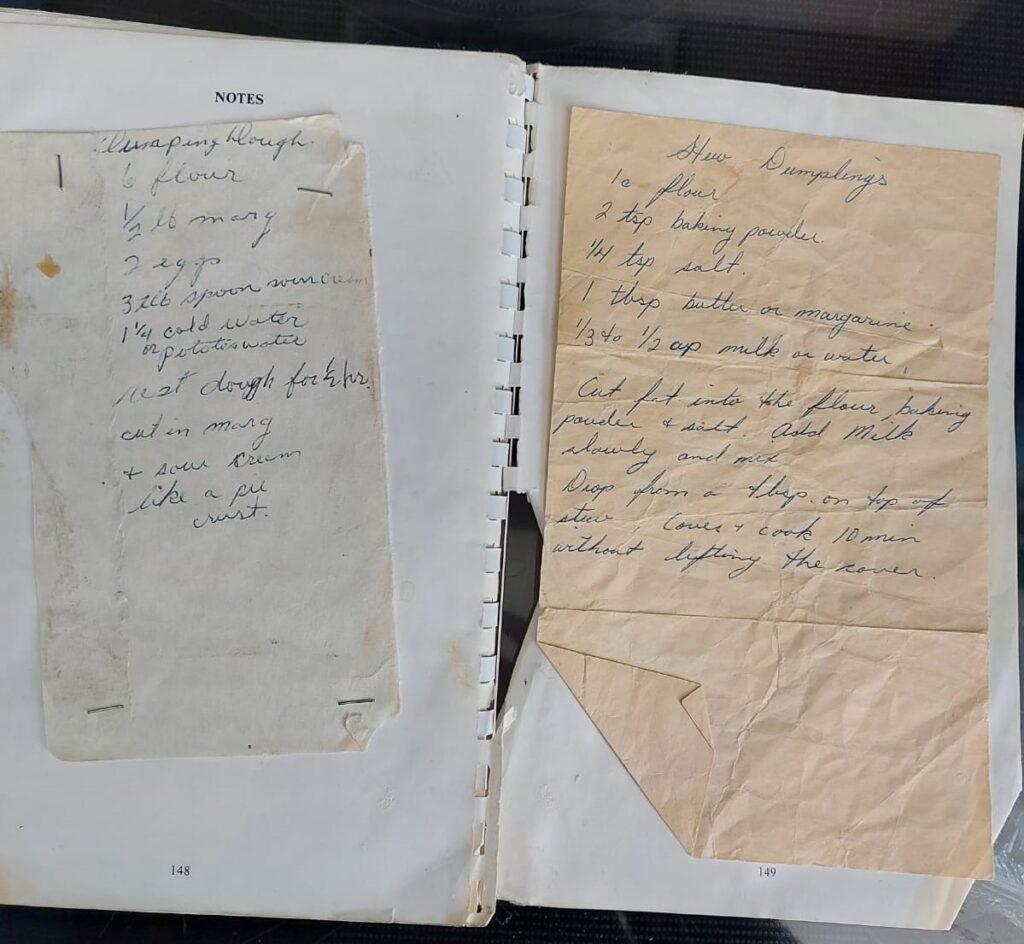

All of the memories that connect me to my Ukrainian-ness are tied to my Grandma’s cooking. The important holidays and often just everyday lunches featured pedaheh (perogies), holopchi (cabbage rolls), and borscht (beet soup). When we would visit my Grandma, I would beg her to make pedaheh. I would help her cut out circles with a heavy bottomed drinking glass from the dough she rolled while sneaking spoonfuls of potato and cottage cheese filling. Of course, she always caught me, but those peppered garlicy bites were worth it!

My Grandma’s pedaheh recipe

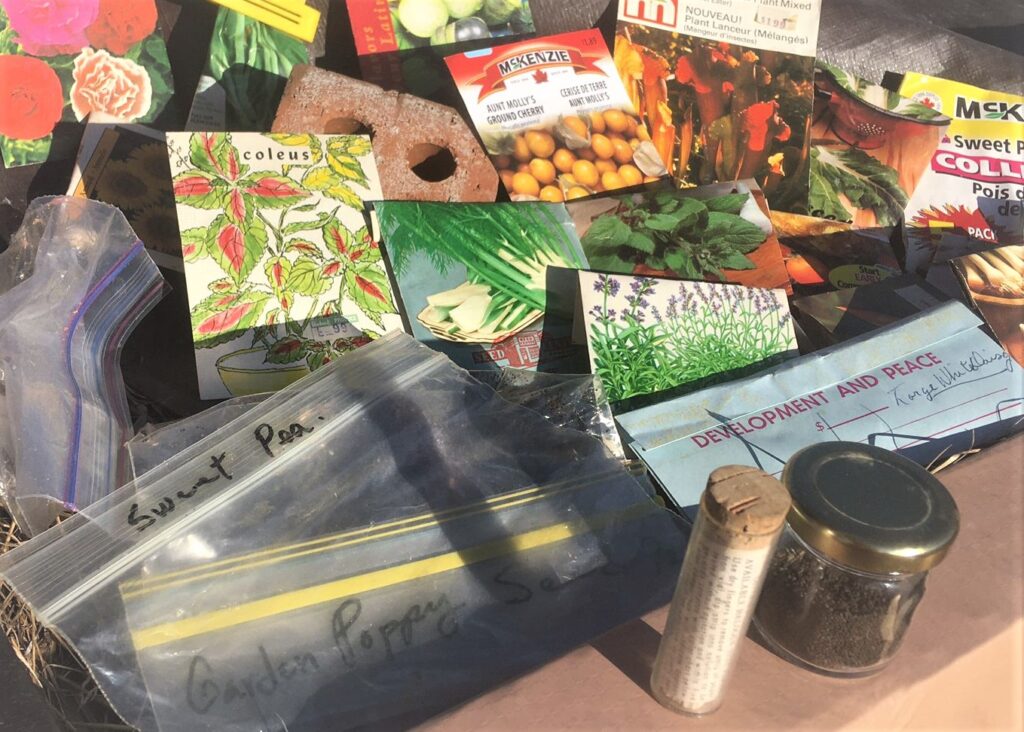

Grandma and her garden at the Bonney Lakehouse

Grandma also planted a garden to feed her family (something her parents and grandparents did when they arrived). She regularly foraged mushrooms and berries, painted ceramics (a Ukrainian folk-art tradition, though she mostly crafted kitschy knick-knacks). And I will maintain that she did write pysanky. I refuse to believe these memories to be untrue. Because, there on my table sits that little ratty Ziploc bag with the kistka, beeswax, and metal poker.

Pinpointing my family’s history was significantly more difficult than reminiscing about my favorite memories. I was able to access my family tree created by my mom’s cousin on Ancestry.org.

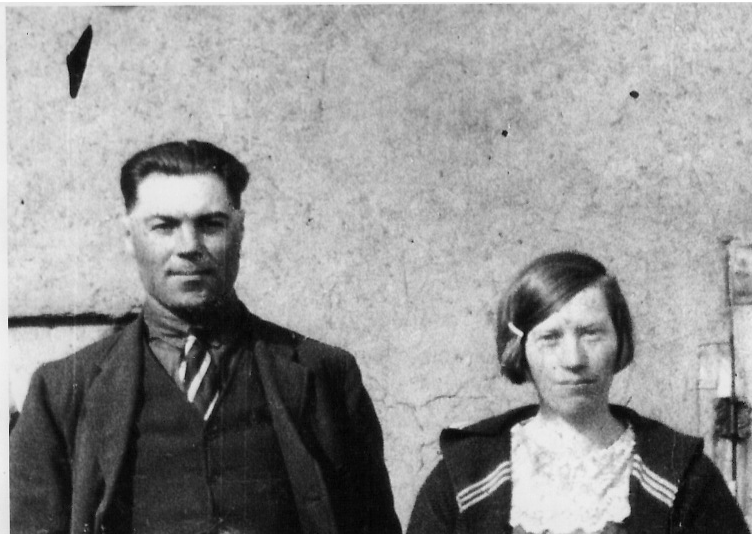

My Grandma’s parents met in Star, AB, and were married in 1923.

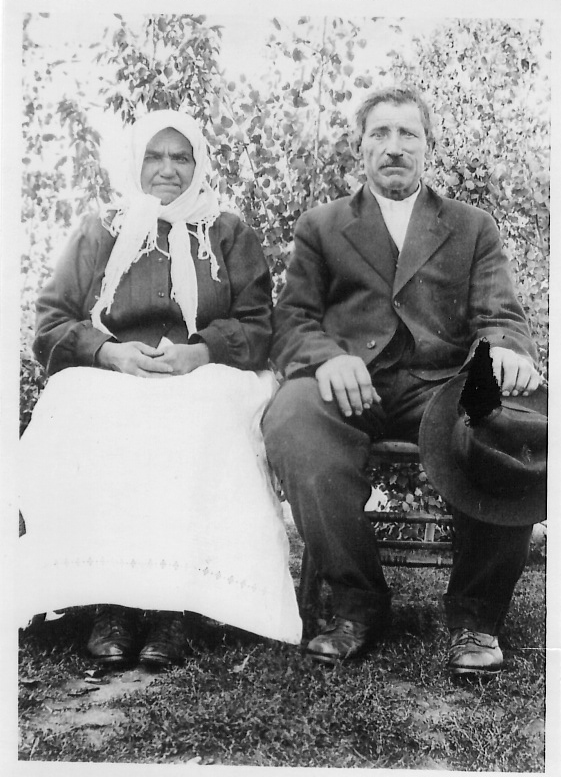

Both sets of her grandparents arrived in Canada from the former Astro-Hungarian province of Galicia. They were part of a first wave of Ukrainian immigrants fleeing the poverty and hardships of the “Old Country” for the promise of land and prosperity in Canada.

My Grandma’s father was an infant when he arrived in Canada in 1900, and her mother was just barely born here—her mother’s family arrived in 1898. Most of my ancestors on this side settled in and around Edmonton. They began a new life subsistence farming on the prairies.

Jan Pruss and Anna Jakubow; My grandma’s maternal grandparents (circa 1910?)

Mikolaj Jakubow and Zophia Zolkiuske; My Grandma’s maternal great grandparents (n.d.)

I also found reference to the old Galician villages of my Grandma’s great-great grandparents. But without searching historic maps, it was impossible to find the exact locations of these towns which are now long-gone. I believe my ancestors to be from around the Sokal’ region.

From the library book, I learnt that Sokal’ pysanky are simple and usually set on a black background- additional design colours are white, red, and yellow which are used to create free-flowing plant and bird symbols. The Sokal’ pysanky lack the ornate designs people may envision when thinking of this folk art.

The two plants that stand out in my mind when I think of my Grandma are poppies and wild strawberries. Last summer, my mom bought me a box of old gardening seeds my Grandma had saved, my mother had hoarded, and I am now storing in a closet. I did not have the heart to tell my mom that these seeds will likely not grow. But, among the collection were thousands of poppy seeds with dates and labels scrolled in my Grandma’s handwriting—some as old as 1977.

Poppy seeds are common in many Eastern European dishes and my Grandma grew them for both their aesthetic beauty and culinary uses. Her garden was often overflowing with the cascading red blossoms.

My mom told me that nearly every summer a police officer would come by and harass my Grandma about her opium garden. I can hear my grandma’s sneering thoughts, perhaps even her scathing words, as she corrected him on his botanical ignorance—these are baking poppies, only an idiot would try to smoke them. She had the dry feistiness of a Ukrainian baba.

As for wild strawberries, they are a flavour forever embedded in my mind. Each spring, at our family cabin near Bonney Lake, AB, I would follow my Grandma through the roadside ditches picking the tiny red dime-sized berries. I would be given a yogurt container and a dollar if I filled it. The process was slow and I think I ate as many as I put in the bucket. By the end of the afternoon, my fingertips were stained red and the jammy flavour of the foraged berries lingered on my tongue. Spending hours picking berries is still something I still like to do, and it remains a pastime that makes me remember my Grandma.

The next Sokal’ symbol I added to my egg was a bird. Birds, particularly hummingbirds, are also something I associate with my Grandma. When I imagine her sitting at her 1950s Formica table—always smoking a cigarette, always with a cup of coffee, always with her soaps droning in the background—I can see her hummingbird feeder through the upper right corner of the glass patio doors. It is full of bright red sugary syrup, and, at a zippy interval, tiny iridescent birds flitter in and out for a sip.

I am not sure I nailed the hummingbird, it kind of looks like a chicken. But, I know what I was getting at.

The final part of my pysanka would be the colours I chose. The Sokal’ tradition would have been to only use white, red, yellow, and black. But, I have included green, and I decided that it was ok since this project was about exploring my ancestry and remembering Grandma.

In the end my egg reflected my memories in a free-flowing design of my Sokal’ ancestors.

I used the kistka from the plastic bag, and the wax that my grandma left behind. I thought about her often as I was writing my egg. I don’t recall when I got that ratty Ziploc of tools, but I am guessing that it was around the time of her death. I have moved and purged possessions over a dozen times in the last 18 years, but this baggy is one of the few things I have kept. There are questions I wish I could ask her, but she is no longer alive to provide any answers. Even if she was, I am not sure that she would.

In reality, there is no point lamenting these lost conversations. In the process of writing this piece and relearning to write pysanky this past Easter I have uncovered many stories and have re-energized a personal interest in my Ukrainian heritage. I may not be able to speak directly with my Grandma, but I can continue to have indirect conversations with her as I continue to explore aspects of our culture.

Perhaps, her roots died when she lost her mother to Multiple Sclerosis at the age of 11? I have been told that her life became much harder after this loss. But, that is where this knowledge ends? My family does not know much about her experiences during this period of her life.

Perhaps, it is more astute to say that she hid them—she hid her roots in the closet tucked away with the rest of the skeletons that neither she, nor my family, talked about.

My Grandma was an enigmatic and guarded woman – she was masked with a hardened exterior. She was also stubborn, tenacious, thrifty, kind, artistic, smoked like a chimney, baked bread, foraged mushrooms and berries, and grew a garden that fed her family of six children. I still don’t buy that my Grandma rejected her Ukrainian roots. My cousin also reminds me about how my Grandma and her sister-in-law would switch to speaking Ukrainian.

“If they did not want us to understand, they spoke Ukrainian.”

I guess, that stupid old language still served a purpose.

If you are looking to try your hand at pysanka, I recommend any one of the dozens of blogs and YouTube channels that provide instructions in this folk-art practice.

Here in Edmonton, the public library has a great collection of books, and so does Orbit Co.

Orbit Co. (The Ukrainian store-10219 97 St NW, Edmonton, AB) is where I picked up dyes, kistkas, and beeswax (4 dyes, a traditional kistka, and a block of wax will cost about $13; besides that, if you have some jars and a few tablespoons of white vinegar, a candle, and some paper towel you are good to go. And don’t forget eggs). There is also EggCessories online, which is a Canadian company based in Toronto and it has several pysanky starter kits.

Recent Comments