Report by Mark Morris

photos: University of Alberta Opera Theatre

Benjamin Britten (1913-1976): Albert Herring Op.39

Cast reviewed (preview performance):

Lady Billows – Wiktoria Jurkiewicz

Florence Pike – Madison Berger

Albert Herring – Gabriel Berko

Mrs. Herring – Angela Bittman

Miss Wordsworth – Andrea Corder

Mr. Gedge, Vicar – Auren Shabada

Mr. Upfold, Mayor – Grayson MacKenzie

Superintendent Bud – Jason Somerville-Knish

Sid, from the Butcher’s – Hendrick Baerends

Nancy Waters – Jane Gibson

Cis – Makayla Forde

Emmie – Shelby DeNeve

Harry – Harmony Handsaeme

University of Alberta Opera Workshop

Directed by Kate Ryan

Conducted by Monica Chen

Convocation Hall, University of Alberta

March 6, 2025

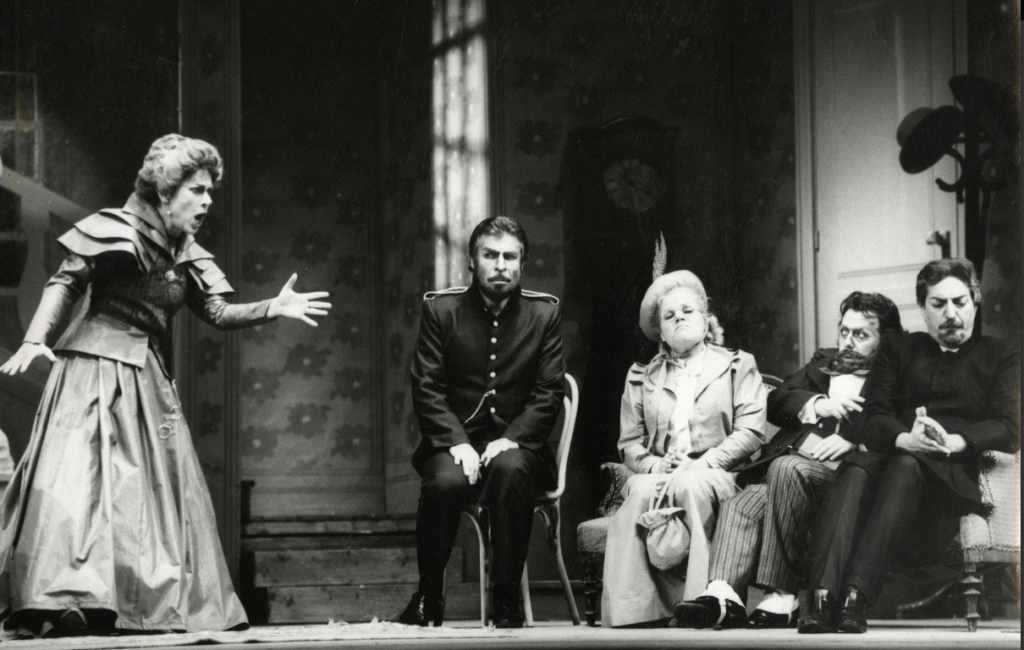

There is a wonderful photograph of a production of Benjamin Britten’s chamber opera Albert Herring by the Greek National Opera in 1985 (reproduced at the end of this review). In it the police superintendent, hunched in his chair, looks suitably chastised, the mayor is cringing on the sofa, the priest is pretending to be aloof, and the schoolteacher attempts to appear superior as all of them are berated by Lady Billows.

What is remarkable about it is that it looks so quintessentially un-British. For Albert Herring is the most quintessentially British of Britten’s operas. Set in the Suffolk area where Britten lived, it is full of topical references to local places, and portrays – and satirizes – provincial small town English life. This in spite of its origin: librettist Eric Crozier (who had directed Britten’s break-through operatic success, Peter Grimes) took the story from Guy de Maupassant’s 1887 play Le Rosier de Madame Husson.

That tells the story of the virtuous Madame Husson, who promotes chastity in her provincial home town of Grisors. She is trying to find a Rose Queen, but none of the young women of the town are virtuous enough. Instead she crowns the village idiot, Isidore. He uses his prize to go off to live it up in Paris.

It was an easy transference to rural England and its class structures. Lady Billows is the harridan who enforces virtuous behaviour, aided by her housekeeper, Florence Pike, who keeps a notebook on everyone’s transgressions. They can find no virtuous young woman worthy of being May Queen for the traditional May Day fête, so, in collusion with the suppliant fête committee (the police superintendent, the mayor, the schoolmistress, and the vicar), they chose the hapless Albert Herring as a May King instead. His friend Sid, a butchers assistant, and Sid’s girl-friend Nancy (whom Albert has a crush on) provide generational support. At the fête Sid spikes Albert Herring’s drink. Albert disappears for a couple of days on what the British would call a ‘bender’ – and in discovering the joys of the pubs he is surprisingly parsimonious with his winnings. When he returns the moral is made: Albert has come of age, and whatever the moralists do, the younger generation will be the younger generation.

The problem with all this is that it can come across as awfully twee – cups of tea with the little finger held out, a rather condescending view of young love – especially when done in British productions, when there is inevitably the temptation to exaggerate the British class stereotypes inherent in Crozier’s version. I am not the only one to feel this: John Christie, the director of the Glyndebourne Festival where the opera was premiered in 1947, reportedly apologized to members of the audience for it (“This isn’t our kind of thing, you know”). Part of the problem is that it was written for very specific singers, with Britten’s partner Peter Pears (who was 37 at the time of the premiere) playing the 18-something-old lead.

Hence the fascination of that Greek photo (nothing twee there). And hence my surprise that the University of Alberta Opera Theatre’s production on March 7-8 (I saw the dress rehearsal on March 6, with the second of two casts) should so successfully manage to avoid that British tweeness, and in doing so give some unexpected insights to the work.

The work has a number of advantages for a student production. There is no chorus (though the Opera Theatre managed to weave in a number of villagers), but instead has a ensemble of 13 characters, none of whom dominate the music. There are few solos, the main one being given to Albert himself. One can get away with – as here – a simple single set that can equally serve (with a sofa) as Lady Billow’s home and (with the addition of laden tables) as the village fête. Similarly, the instrumentation is for chamber forces: a 12 piece orchestra with the conductor on the piano. This production sensibly pulled this back to eight all women players, cutting the harp, and utilizing a keyboard as well as the piano. The overall scale of the production thus entirely suited the stage of Convocation Hall.

All that being said, the opera was written for some of the best orchestral players in the UK (my uncle was the flautist in the premiere), and presents some considerable challenges, especially in the horn writing (it was written for one of the greatest horn players of the 20th-century, Denis Brain). Britten also wrote for some of Britain’s best singers, and some of the multi-voice writing reflects that.

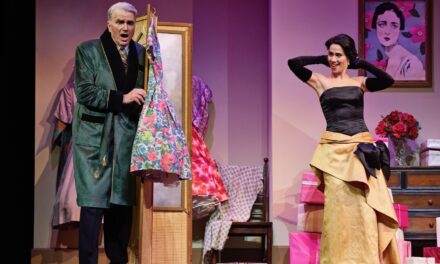

The occasional understandable hiccup here and there notwithstanding (this was a preview performance), the University forces carried this off with student aplomb, clearly revelling in the humour of the piece. The vocal forces ranged in experience from the bass of guest Jason Somerville-Knish (Superintendant Budd) – he started with the Edmonton Opera Chorus, trained at UBC, and has appeared in the Fringe – to the Lady Billows of Wiktoria Jurkiewicz, who was, I understand, appearing on the stage for the very first time (though you would not have known it from her assurance). Gabriel Berko, one of alternating Alberts for the performances, had to assume them all, owing to the illness of the alternate – and a fine figure he made, with a kind of stubborn gravitas at the beginning that suggested the possibilities of an eventual rebellion, while at the same time putting across the innocence of the character.

But it would be invidious to further highlight individual singers, for this was very much a group performance, and one consistent in its standards. Indeed, some of the most effective music-making came in the big concerted passages – how well Britten does write these, alternately sarcastic and thrilling. All the voices were miked, and were very effectively balanced, so there was no sense of strain that can occur with younger voices in a larger hall.

There had been a suggestion that the setting would be transferred to Alberta, but – wisely I think – this was dropped (the legacy did explain the Superintendent’s uniform). The very fact that there was also no attempt at British accents was actually an advantage: the work came across as a parable that was universal, rather than too closely confined to place. There was an advantage, too, in having all the singers from the same age range as the chief protagonist: the story then becomes more about the coming of age of Albert, Sid, and Nancy, and less a satirical slice of stereotypical English life.

Of course, the purpose of such an opera workshop – this was the course’s eighth annual full-length opera production – is to give those younger singers (who included students from other faculties besides Music) experience, both vocal and theatrical, in a full-length work. The singers themselves might argue that it is also to entertain their audiences, and this production certainly did that.

But this is, after all, a university, and, intended or not, there were some unexpected and more academic insights into Britten’s work. The first was that – in part because of the age range and nationalities of the performers – the work came across as more stylized than stereotyped. In doing so, its theatrical antecedents in the stylized political work of such playwrights as Christopher Isherwood and W.H. Auden (with whom Britten had worked) were brought out. It was a theatrical style he never really attempted again, for it essentially belonged pre-War. The second was how many reminders in the score there are of earlier Britten works: strong echoes of elements of Peter Grimes in the village banter (“Good morning, good morning…”), and too of the Serenade for Tenor, Horn, and Strings, written for Pears and Denis Brain six years earlier, especially in the horn writing but also in the vocal lines. But essentially it was the end of a theatrical and musical strand in Britten’s work: the next opera was the very different masterpiece, Billy Budd (1951).

All in all, this enthusiastic student production ticked all the boxes: entertainment for the audience, challenge and experience for the performers – not to mention the esprit de corps required for such an ensemble piece – and, for the academics, a little to ponder on in the nature of Britain’s only comic opera.