The ageless comedy reset in the film world of the 1950s

Review by Mark Morris

Donizetti: Don Pasquale

Don Pasquale: John Fanning

Dr. Malatesta: Phillip Addis

Ernesto: John Tessier

Norina: Lucia Cesaroni

Notary: Ryan Nauta

Director: Stephania Panighini

Set design: Scott Reid

Lighting design: David Frazer

Costume design: Heather Moore

Calgary Opera Chorus

Calgary Philharmonic Orchestra

conducted by Jacques Lacombe

Jubilee Auditorium South, Calgary

Wednesday, February 5, 2024

There is darkness lurking somewhere at the heart of all the greatest comedies, though one doesn’t expect to find it in Donizetti’s 64th opera, Don Pasquale, tossed off in the space of a couple of weeks in 1843.

Indeed, I don’t think Calgary Opera intended to bring it out in their entertaining, inventive, fast-paced, and ultimately thoughtful production at the Jubilee Auditorium South, which I saw in the second performance on February 5th. But that’s what they did, with an all-Canadian cast and company, apart from the Italian director, Stefania Panighini.

The opera is based around one of the oldest of tales: the old man who is to marry a young woman, who herself has a young beau she wants to marry. One can happily trace the type from Roman comedy, through commedia dell’arte, to Angelo Anelli’s libretto for Stefano Pavesi’s 1810 opera Ser Marcantonio, whose story Donizetti and his librettist Giovanni Ruffini pinched for their opera.

The twist to Anelli’s version of the tale was that the planned marriage between the old man and the young woman is totally fake, set up to make a fool out of him, as opposed to the usual trope of the young woman trying to extricate herself from a marriage arranged by her father.

Since the story is timeless, and since, as an interesting essay in the production program booklet points out, Donizetti and Ruffini did not specify a time period for the opera, it is an ideal candidate for setting it in a different era. As that essay says, “While change for its own sake – or worse, for shock value – is not useful, successful resettings can provide a sparkling adaptation to a beloved classic”.

Director Panighini, herself also a videographer, takes her cue from the vibrant Italian post-war film world. Scott Reid’s set is a film studio to the right, and, on a raised stage to the left, a costumes area where the old man Don Pasquale holds court. That it is Italy is clear from the black-and-white silent-movie that accompanies the overture, and which features the main singers. It is a very effective opening, even if the black-and-white silent format did cause momentary confusion as to the era in which the opera was reset.

The appearance of a real Vespa, cunningly used for the duet between Norina, the young woman (soprano Lucia Cesaroni), and her lover (tenor John Tessier), confirms the period as the 1950s, and recalls Audrey Hepburn and Gregory Peck in Roman Holiday. There are discrete period updates in the English surtitles (Don Pasquale complains about Norina wanting a car), but otherwise they are a close translation of the original (even the expression ‘dead man walking’, which one might think is an oblique movie reference, is in the Italian libretto: “un morto che cammina”). Costumes by Heather Moore are clearly from the poodle skirt era.

A number of the arias take place on the film set, with flown-in stereotypical backdrops, film camera people shooting the solo scene, and even a stage-hand bringing in a fan to billow up Norina’s skirt, in Marylin Monroe style. Norina herself seems to be a film starlet, and her lover Ernesto a would-be leading man. Particularly imaginative is the chorus staged as an audition, with the servants coming one by one in front of producer Dr. Malatesta (baritone Phillip Addis) and quickly being dismissed – excellent singing, too, from the 12-strong chorus.

It is all great fun, with the modernist incongruity of the snippets being filmed and the disconnected backdrops giving a whiff of Italian art film. The Calgary Philharmonic were in fine form in the pit, with Jacques Lacombe, whom I had not heard before, conducting with verve and colour – and neatly adjusting in the couple of moments when awkward sight-lines threatened a disconnect between singer and orchestra.

The wonderful long trumpet solo that opens Act II inevitably brings The Godfather to mind, and Tessier had just that flavour, creating a real character out of what is in many ways a thankless role, as the poor man keeps being sidelined by the other characters. One could well see his Ernesto somehow stumbling into the clutches of the mafia and ending up in that opera house in Sicily. He also has just the right Italianate tenor for the role, and it was a pleasure to hear him in such strong form.

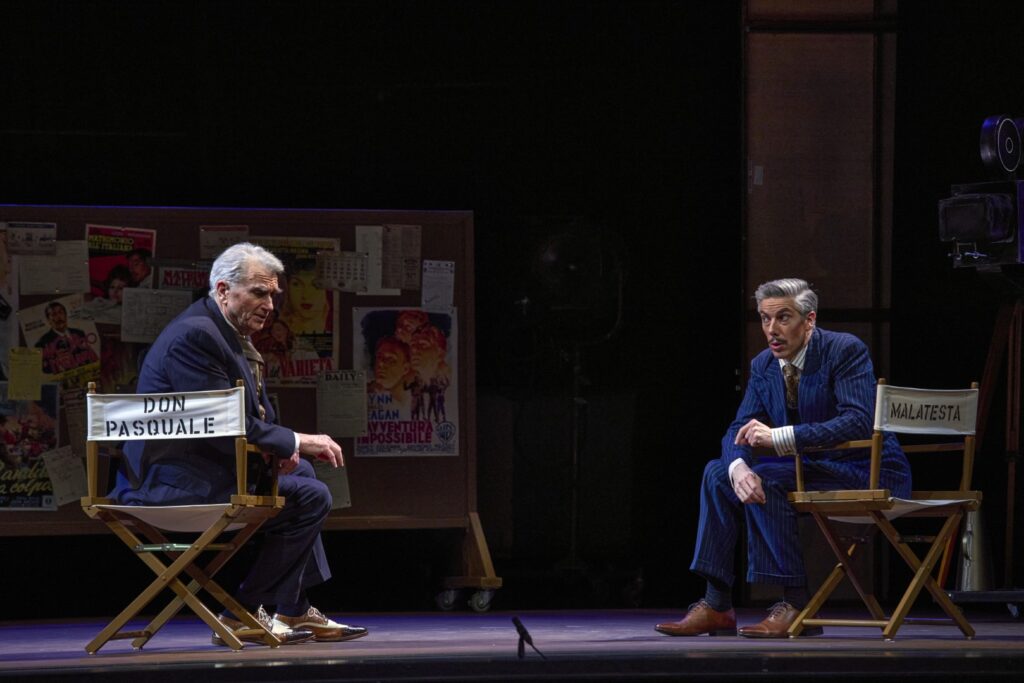

The most complete performance, though, came from Addis. His Dr. Malatesta was entirely believable, both vocally and in his acting, as a kind of entrepreneur cad, dapperly dressed, for all the world looking (and acting) like Vince McMahon of WWF wrestling infamy. The 70-year old John Fanning came out of retirement to sing the title role. The veteran Canadian baritone, and later bass-baritone, is vocally not as flexible as he once was in the very fast patter singing, but that suited the role (Don Pasquale himself claims to be 70). There was absolutely nothing lost, though, in his thoroughly convincing acting – one knew exactly what he was thinking and feeling from and expression and body language alone. The interaction between Pasquale and Malatesta, both sitting in director’s chairs on the film set, was the highlight of the evening, both men wanting something out of the conversation, both men thinking they knew what the other was thinking – a real theatrical as well as operatic moment.

What all three singers brought to their roles was the creation of characters deeper, more rounded, than is so often the case with this kind of comedy, when the foolish old man, the villain, and the young tenor can all too easily seem stereotyped. Cesaroni’s approach to Norina was somewhat different. Here was a stereotyped character, the flirty starlet, and it was well done and well sung. But the character was established early on, and didn’t develop. There are suggestions in the libretto (and score) that she does have moments of self-questioning, but she didn’t here. She seemed to relish in the destruction from start to finish, with considerable energy. The result was that, especially given the more naturalistic body language of Fanning and Addis, I for one actually felt sorry at one point for Don Pasquale.

By the end that feeling was only amplified, with the downcast old man giving in to blessing the marriage, not really fully aware of what just happened. Consequently the opera ended with something of a whimper, as if Panighini did not quite know what to do with it – a cynic might say, entirely appropriate for a 1950s Italian art film.

None of this stopped the fast flow of the comic entertainment – it just gave that hint of an undercurrent of darkness that left one thinking a little differently about the whole proceedings, and adding an extra dimension of appreciation.

Calgary Opera also announced their 2025-2026 season in the program booklet. There are three popular favourites: Madama Butterfly in November, Hansel and Gretel in January and February 2026 (with a puppetry component), and The Barber of Seville in April 2026. The fourth production, in November/December 2025 is an opera for younger audiences, Little Red Riding Hood, by the American composer-librettist Seymour Barab (1921-2014), who specialized in such tales, and was also a long-time member of the Philip Glass Ensemble.

In the meantime, Calgary Opera continue their current season on April 5 with what is for me the the greatest comic opera ever written, Puccini’s one-act Gianni Schicchi, in a very contrasting pairing with Bartók’s operatic masterpiece, the dark, symbolist, and at times extraordinarily beautiful Bluebeard’s Castle.