Review by Mark Morris

Sophie-Carmen Eckhardt-Gramatté (1899-1974)

Caprice No. 1 for solo violin “Die Kranke und die Uhr” (The sick woman and the clock)

Laura Veeze, violin

Alissa Cheung [b. 1985]

Analogia [(2012) for two violins

Alissa Cheung, violin; Laura Veeze, violin

Dame Ethel Smyth (1858-1944)

Cello Sonata in A Minor, Op. 5

Meran Currie-Roberts, cello; Sarah Ho, piano

Kati Agócs (b. 1975)

Every Lover Is A Warrior for harp

Nora Bumanis, harp

Jennifer Higdon (b. 1962)

Light Refracted for clarinet, violin, viola, cello, and piano

Alissa Cheung, violin; Laura Veeze, viola; Julianne Scott, clarinet; Meran Currie-Roberts, cello; Sarah Ho, piano

Muttart Hall

Sunday, March 10, 2024

The concerts put on by the Edmonton Recital Society are always of interest, but their fourth concert of the current season, in the Muttart Hall on Sunday, March 10, was particularly felicitous.

For it celebrated International Women’s Day (March 8) by not only having a concert of music composed entirely by women, but also played entirely by women, and, indeed, played entirely by Edmonton women.

The works were well selected, too, because although a couple of the composers may have been familiar by name, I doubt if many of the audience had heard many pieces by them before – so it was also a concert of discovery.

After initial remarks by the musicologist D.T. Baker – more about these later – it opened with the violinist Laura Veeze lovingly playing a caprice for solo violin by Sophie-Carmen Eckhardt-Gramatté. We don’t hear enough of her music these days, though she was one of the most influential Canadian composers after World War Two, and a fierce supporter of contemporary music.

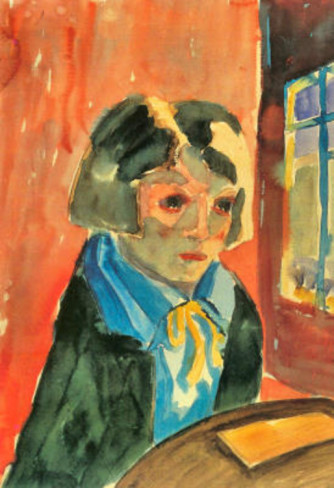

She had a colourful life as a composer, virtuoso pianist, and violinist – she was born in Russia in 1899, studied in Paris, and then gave concert tours in Western Europe, which included her own works. She married the German expressionist painter Walter Gramatté in 1920, lived in Spain studying with Pablo Casals from 1924 to 1926, and toured the U.S.A. with great success in 1930, her husband having died in 1929.

She married again in 1934, to the art historian and writer Ferdinand Eckhardt. She spent the war with her husband in Vienna, and they moved to Canada and Winnipeg in 1953, where, apart from some teaching, she devoted her life to composition. In 1974 she was the first Canadian composer to receive the Diplôme d’honneur of the Canadian Conference of the Arts.

(date unknown)

The Caprice Veese played is the first in a set of 10 Caprices for solo violin, written over a decade from 1924 to 1934 – all of which have titles evoking some aspect of Eckhardt-Gramatté’s life. ‘Die Kranke und die Uhr’ (The sick woman and the clock) reflected her experience being at the bedside of a sick friend, and being aware of time ticking away. It has something of a gentle wistful dance, with elements of a European lark ascending – a most attractive and thoughtful way to start the concert.

The violinist and composer Alissa Cheung is these days a violinist with the famed Bozzini String Quartet, working internationally and across Canada from its base in Montréal. But she is also very active as a composer, and almost invariably brings a performance of one of her works when she makes a welcome return to Edmonton.

The two movement, 10-minute Analogia is a relatively early work, written for the Anne Burrows Foundation Concert of 2012, where it was originally performed by Cheung and Edmontonian Ewald Chung (a performance that can be seen on YouTube). The first movement, ‘Riflettare’ (meaning to ponder), flowed well from the wistfulness of the Eckhardt-Gramatté, the slow lines of the two instruments lapping in constant metrical steps around each other, with a suggestion of tonal potentials that don’t quite lead to resolution. After a more dissonant moment, the music gets sparer and sparer, eventually, rather like a late Shostakovich work, fading away. It would be interesting to know what the inspiration was for the the second movement which carries the title ‘Il Passo Falso’. This can mean a false step in Italian, or the equivalent of ‘faux pas’. The false step would seem to be more plausible, because it is a quirky, 3-minute little dance, with some little false steps in it, a kind of Soldier’s Tale dance in Dr Martens boots. It was authoritatively played by the composer and Veese (a stronger performance than that premiere on YouTube).

bottom, left to right: Meran Currie-Roberts, Julianne Scott, and Sarah Ho

photo: Edmonton Recital Society

The first half ended with a performance by that wonderful colossus of a character, the composer Dame Ethel Smyth. She was the first woman composer to be created a Dame (the equivalent of a knighthood), she was a suffragette, she spent two months in prison for her activities, she was an avid golfer, and she had a number of affairs, mostly with women (those with whom she fell in love with included the chief suffragette Mrs. Pankhurst and Virginia Woolf). She studied at the Leipzig Conservatory, and was encouraged in her composition by Arthur Sullivan. Her 1906 opera The Wreckers is, in my opinion, the best English opera between Purcell and Britten, while her Mass in D (1891) for soloists, chorus and orchestra with organ, an advanced work in the British context of its time, is perhaps the finest of all British 19th-century choral works apart from Elgar’s The Dream of Gerontius.

It was thus a most welcome opportunity to hear her three-movement Cello Sonata in A Minor, Op.5, written in 1887 when she was a student in Leipzig (not to be confused with her even earlier 1880 Cello Sonata in C minor). It does not therefore represent her mature voice, but is an indication of her prowess in a late-Romantic idiom. After its lovely flowing Romantic opening, what was striking in both the first and the last movements was how effectively and unexpectedly the two instruments switched roles, and the cello provided bass support for the piano.

The Brahmsian middle movement (she had met the German composer in Leipzig) seems the most conventional, until it takes flight in a middle section. The final movement starts with a suggestion of the hunt (Smyth was an avid horse-woman), and ends in high and joyful energy. Meran Currie-Roberts and pianist Sarah Ho gave a persuasive and lyrical performance, which will, I hope, have encouraged the audience to discover more of the music of this major woman composer. Listeners should note, though, that although Baker, when introducing her, repeatedly pronounced her name as ‘Smith’, it is actually pronounced Sm-y-the (/smaɪθ/).

The work which opened the second half of the concert was perhaps the least interesting in the program, though harpist (and President of the Edmonton Recital Society) Nora Bumanis played it with the skill and dedication she has always shown, both as the Principal Harpist of the Edmonton Symphony Orchestra and as a soloist.

The 49-year old American-Canadian composer Kati Agócs teaches at the New England Conservatory of Music and keeps a work studio in Newfoundland, and this was the first time I had come across her music. Her Every Lover Is A Warrior was written in 2006, and is a cycle of three short works for harp, inspired by different cultures and ostensibly reflecting themes of lovers and war, though the connection of the rather charming and gentle middle movement, based on a French hymn, was unclear.

The cycle was perfectly pleasant, but its limitations were exemplified by the first piece, based on the Appalachian tune John Riley, which tells of a soldier who returns after eight years of war, to find his sweetheart still faithful. Agócs claims she has created a Bluegrass piece, but I couldn’t hear anything Bluegrass at all, nor could I discern any musical rendering of the story.

The final piece was by a much better known American composer, Pulitzer Prize-winning Jennifer Higdon, who was born in Brooklyn, and has won three Grammys (all for concertos). Light Refracted, composed in 2002, is a two movement work for string trio, clarinet and piano. The material came from an orchestral work, blue cathedral.

“After it was premiered,” she has written, “several individuals pointed out to me Monet’s cathedral paintings, one of which is completely in blues. I became fascinated with the idea that painters often paint a particular subject in varying degrees of light (as Monet did). I wondered if composers could do the same thing. So when I started Light Refracted, I decided to take the musical elements used in blue cathedral, and recast them in a different light. It was extremely difficult, but also an interesting challenge. Like Monet, I tried to examine the melodies, rhythms, harmonies, and orchestration in a new context. So the first movement reflects that “artistic” study and manipulation.”

Claude Monet The Portal of Rouen Cathedral in Morning Light, Harmony in Blue (1894)

That first movement, titled ‘Inward’ reflects “on our inner light, and how we take that light in”, and the second movement ‘Outward’ is “the opposite, our projection of light out to the world”. In style the work is neo-Romantic, opening with a low, slow clarinet solo, and that first movement is initially rather rhapsodic, with beautifully judged entries of the different instruments. Agitation grows, with a very strong sense of the different instruments as individual voices, tangling around each other, until a rather lovely gentle close.

The second movement, Outward, as one might expect, is in complete contrast, with buzzing scoops against a scurrying piano – fast, furious, and fun. It somewhat looses its way in the middle, but returns to the opening ideas in a kind of frolic of light. It can’t be that easy to play, but Cheung, Veese, Currie-Roberts, Julianne Scott, and Ho, pulled it off with aplomb, ending a fine, inventive concert.

However, I cannot, as a critic, ignore the comments by D.T. Baker at the opening of the concert. He apologized for the first piece on the program, referring to the events at Winnipeg’s main art gallery. Unfortunately, he did not fully explain those events, to the apparent mystification of much of the audience.

He ended up by saying we could learn from them. Yes, indeed we can, though not in the way Baker intended. What he was referring to was an article in The Walrus late last year that went into the activities of Sophie-Carmen Eckhardt-Gramatté’s husband, Ferdinand Eckhardt, during World War II, and outed him as a Nazi. Eckhardt was appointed director of the Winnipeg Art Gallery in 1953, curating over 650 exhibitions, and supervising the building of the current gallery. Following the Walrus article, the Gallery dropped his name from its main entrance hall, website and all other gallery materials, and is investigating whether there is any Nazi-looted material in the Gallery (they haven’t found any so far).

Eckhart was, indeed, one of the 88 writers who signed the pledge of allegiance to Adolf Hitler in 1933, when Hitler became Chancellor. He did indeed work in I.G. Farben in the late 1930. He was drafted into the German Army from 1942 to 1944. But all of this had been openly acknowledged.

As has been pointed out, every German who did not leave in 1933, and every German who fought in the war, could be tarred with the same brush. Better-known artists and art critics, if they wanted literally to survive, had to take a similar oath, what ever one might think of that in hindsight. Ekhardt was vulnerable – he had published a treatise on the graphic work of Walter Gramatté in 1928, and in 1932 he organized a Gramatté memorial exhibition. Gramatté was exactly the kind of expressionist artist Hitler hated – indeed, his work was condemned by the Nazis the very next year as ‘degenerate’.

While Eckhardt was at Beyerwerke, a subsidiary of I.G.Farben, he was primarily responsible for the marketing of acetylsalicylic acid – aspirin to you and me.

As far as I can gather, there has never been any suggestion that Eckhardt knew anything about, or was involved in any way with, Nazi atrocities. After the war he seems to have been immediately reinstated into the kind of work he did before the war, becoming head of the Department of Education at the Vienna State Collections, and co-founding the Austrian-American Society, of which he was Director. He was buried in 1995 beside his wife in Berlin, where he has an Honorary Grave. Berlin Honorary Graves are awarded to deceased persons who have made outstanding achievements during their lifetime with a close connection to Berlin, or who have rendered outstanding services to the city through their outstanding life’s work.

One can hardly imagine the German authorities, so sensitive to their unfortunate past, allowing this to stand if there was any suggestion that Eckhardt was a war-crime Nazi, or even a die-hard one.

What has all this got to do with this concert? Baker was insinuating that the activities of the Winnipeg Art Gallery had shown that Eckhardt was a Nazi, and because he was a Nazi, we should have nothing to do with him. Therefore we should have nothing to do with his wife, Sophie-Carmen Eckhardt-Gramatté, and therefore even playing one of her works had to be the subject of an apology.

What did we learn from this? That cancel culture has gone too far when it puts forward censorship like this (and Canadian art galleries do seem to be at the forefront of such political correctness). If someone can show that Eckhardt supported the Nazi government cause any more than so many other Germans, fair enough – but to the best of my knowledge no-one has. But to then blacken his wife as well, with no evidence whatsoever, takes things too far.

Quite apart from anything else, and with the proviso that the Eckhardts did not in the war do anything horrific (and there is no suggestion that they did), Canada is a caring and benevolent society. I would have thought that the really considerable achievements in Canada of both husband and wife, and the commitment they gave to Canada, can redeem them in our eyes, and we can celebrate those achievements, while noting they did live in Germany and then Austria during the Nazi period, which they never denied.

This unfortunate introduction to the music was the one sour note in what was otherwise a very fine concert indeed.