Photo by T. Charles Erickson

review by Hannah Rennie

On November 19, I went to the Northern Alberta Jubilee Auditorium for the closing night of a musical I’ve been dying to see: Hadestown. The musical, which originally premiered in 2006 before being revised in 2017, is a retelling of the ancient Greek myth of Eurydice and Orpheus. The show has since made it to Broadway in 2019, and has received eight Tony Awards as well as a Grammy Award. I’ve studied the myth of the doomed lovers at university, in an introductory Classics course, but nothing prepared me for what Hadestown had in store.

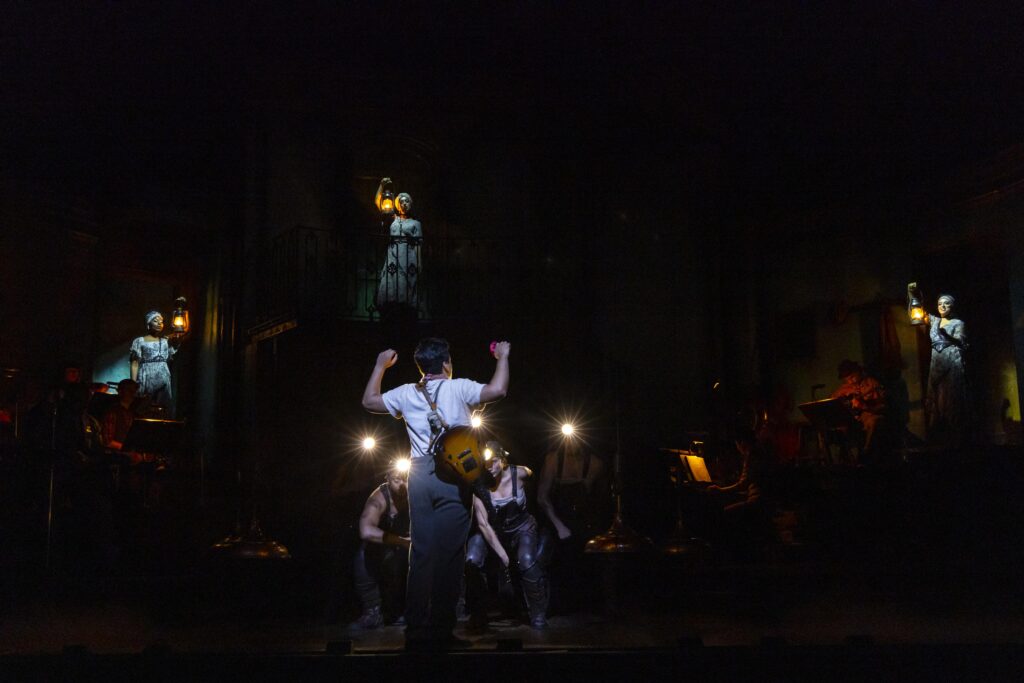

Written by Anaïs Mitchell and directed by Rachel Chavkin, the play puts a steampunk spin on the original myth. The story is narrated by Hermes (Will Mann) and set to swinging jazz music, performed by the on-stage orchestra. The set is relatively nondescript, with an open floor, risers for the orchestra on either side, and a balcony where Hades (Matthew Patrick Quinn) and Persephone (.) overlook the other characters. However, dramatic lighting and fog transforms the stage into a factory floor when Eurydice (Amaya Braganza) and Orpheus (J. Antonio Rodriguez) descend to Hadestown. Combined with the ragged overalls and mining headlamps of Eurydice and the other workers (i.e. the Chorus), these effects turn the static set into an industrial hellscape.

Although the play is essentially a retelling of the age-old myth, it is set in an unnervingly contemporary world. Mitchell, the playwright and songwriter who created Hadestown, describes the setting as a “darkly political, Americana dreamscape”. The regular world has become warped by extreme weather and increasing poverty, while the Underworld—known in the play as Hadestown—is a dark and heavily industrialised realm full of monotonous labour and soulless slaves. While the play is a mostly-accurate retelling of the myth, it is also layered with political critiques that add a whole new depth to the ancient story.

Photo by T. Charles Erickson

In the original myth, Eurydice is killed by a viper and thus descends to the Underworld; in the musical, however, she decides to make a bargain with Hades. In exchange for asylum from the hunger and cold that plague her in the overworld, she will go to Hadestown and labour for Hades for the rest of eternity. In other words, Eurydice is literally giving up her life to spend her days working.

In the song ‘Why We Build the Wall’, Hades suggests that Eurydice has chosen freedom by coming to the Underworld: “The enemy is poverty / And the wall keeps out the enemy / And we build the wall to keep us free”. This begs the question, though: what kind of freedom is there to be had when one is caught between a rock and a hard place? What kind of “life” is it to live in a state of eternal purgatory? Mitchell’s depiction of Hadestown is as much a cunning critique of late-stage capitalism as it is a unique twist on Eurydice’s story.

However, Hadestown’s political commentary does not end there. Through her use of music and myth, Mitchell weaves an environmental allegory throughout the play. In the original mythology, Persephone (Hades’ wife) splits her time between the living and the dead. When she’s above ground with her “suitcase full of summertime”, life flourishes; when she’s below, the world goes cold and dark. The myth of Persephone was originally meant to explain the changing of the seasons. Mitchell, however, puts a spin on the original story, and suggests that the ancient balance has been struck off kilter.

The more time that Persephone spends among the oil drums and industrialised factories of Hadestown, the more drastic the weather changes become. As described in ‘Any Way the Wind Blows’, “the weather ain’t the way it was before […] It’s either blazing hot or freezing cold”. Hence, Mitchell has found a way to depict climate change through the classic myth.

As for the solution, Orpheus suggests that the answer is to be found in the arts: he is writing a song that will “Take what’s broken, make it whole / A song so beautiful / It brings the world back into tune” (‘Come Home with Me’). Not only does he think that this song will bring about spring and fix the drastic weather, but he sings it to Hades and Persephone in a plea to be allowed to take Eurydice away from this industrialised hell and back to the world of the living.

As in the myth, Hades agrees on one condition: Orpheus can lead Eurydice back to the surface so long as he doesn’t look back. As they walk, Eurydice sings to Orpheus to remind him that she’s there. In a moment of doubt, though, Orpheus looks back, condemning his lover to a life in the Underworld. Like the myth, the play is a tragedy, and ends with Eurydice being summoned back to Hadestown where she will remain forever.

However, I think that Mitchell’s play is ultimately meant to be a hopeful one. It is certainly dark and foreboding, but it also sows a seed of possibility: that perhaps, one day, we can move beyond this hellish capitalistic world and solve this climate crisis that we’ve created before it’s too late.

As Orpheus’ journey suggests, there is strength and unity to be found in the arts; however, our efforts will be fruitless unless we are able to walk hand in hand. If we take anything from the tale of Eurydice and Orpheus, it should be that solidarity and unwavering hope are key.

I was absolutely fascinated with the political undertones of Hadestown, and would go see it again in a heartbeat. However, you don’t have to look that deep to simply enjoy the story and appreciate Mitchell’s brilliant retelling of the original myth. The music is lively and excellent, and pairs perfectly with the diverse cast of voices: from Hermes’ baritone to Orpheus’ sweet and melodic voice, each performer perfectly complements their role. The acting itself was flawless and moving, and the play overall was the perfect execution of Mitchell and Chavkin’s vision. So whether you are looking for a deeper commentary on contemporary social issues, a taste of Ancient Greek mythology, or simply a good musical, I highly recommend checking out Hadestown.

Photo by T. Charles Erickson

Click here for another edmonton scene review of Hadestown