The 2022 Tanya Prochazka Memorial Concert

Tanya Prochazka Memorial Concert

Kathleen de Caen (Cello)

Janet Scott Hoyt (Piano)

Claude Debussy: Sonate (1915)

Robert Rival (b. 1975): Sunshine Variations (Premiere performance)

Edmonton Recital Society commission in memory of Tanya Prochazka

David Popper: Hungarian Rhapsody Op. 68

César Franck: Sonata in A major (1886)

Edmonton Recital Society

Muttart Hall, Alberta College Campus

Sunday, September 25, 2022

It may have been a long time coming, but it was well worth the wait!

The young Edmonton cellist Kathleen de Caen, who now is a member of the Calgary Philharmonic, had been chosen to give the 2020 Tanya Prochazka Memorial Concert in honour of the distinguished cellist and teacher (and former Artistic Director of the Edmonton Recital Society), who died in 2015. Then Covid hit. The concert, scheduled for March 15, 2020, had to be postponed. Into limbo it went, until two-and-a-half years later, on September 25th, it emerged in some splendour at the Muttart Hall.

De Caen (a former pupil of Prochazka) and her pianist, Janet Scott Hoyt (a longtime friend of Prochazka), had chosen a formidable program of four substantial works, each demanding in their own ways.

Of especial interest was a brand-new work, commissioned for this concert, by Robert Rival, Edmonton Symphony Orchestra’s Resident Composer from 2011 to 2014, who is now based in Ottawa. Sunshine Variations had a rather unexpected influence: Sir Hubert Parry’s 1897 Symphonic Variations. That bubbling late-Romantic work is cheerful almost throughout, with a constantly propulsive set of rhythms, and a series of short, seemingly unstoppable, variations on a short theme.

Rival’s Sunshine Variations, written in the winter of 2019, picked up on all these ideas, as if reimagining such basics for a later century and for his own personal style. The gently unfolding theme, itself built on a five-note kernel, is given by the cello playing solo, and is then followed by 21 short variations. The overall feel is indeed very sunny, especially with an opening in that sunniest of keys, C major. Rival suggested that the listener might not be able to hear all the variation changes, but in fact they are pretty clear, while at the same time regularly eliding into a new variation – very skillfully, for this is a beautifully crafted work that will appeal to those who enjoy musical construction as much as it will to those who want their ears to be charmed.

Rival does not attempt to extend the boundaries of either cello or piano, but does include moments of high harmonics on the cello, and there is one fascinating variation, near the centre of the piece, where the piano plays an entirely minimalist solo. Otherwise, his intention is indeed to be sunny, and it is. The two instruments are, after the solo opening, very much equals, sometimes playful, at times a little whimsical, and almost always lyrical. Rival of course could not possibly have known when he wrote it, but these happy variations turned out to hit exactly the right optimistic tone for coming out of Covid. Synchronicity at work here.

One feature in particular contributed to that optimism: throughout the different variations (and in the theme itself), the musical lines regularly rise up the register, giving a flow that rises up and then starts again. Only in the darkest variation does the cello line fall, the piano playing blocks high on the keyboard, but even then, the cello can’t resist also ending up high. Finally, at the very end, everything happily tumbles downward, and in the contrast, in the change of the repeated flow, we know the piece is ending.

These Sunshine Variations were a very pleasant surprise – they deserve to become popular with both cellists, who will really appreciate the musicality of the writing, and with audiences, who will enjoy their flow and their happy tone.

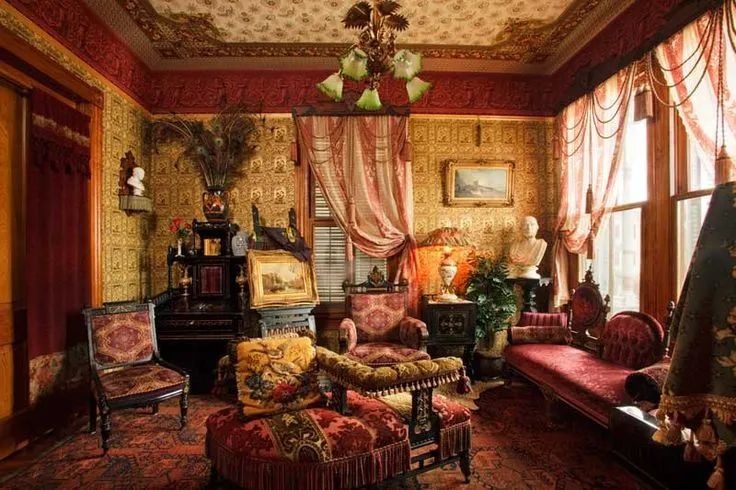

The other outstanding performance took up the entire second half of the recital. For me, the music of César Franck so often conjures up a kind of late-Victorian cornucopia, like the over-abundant and sometimes overwhelming decoration of a Victorian living room: rich colours, heavy velvets, mass on mass of detail, with not a spot of stasis to be seen. Perhaps this is the reason why his music is not as well-known as it deserves: he is not a late-Romantic who appeals to the emotions – one can’t imagine anyone taking out a handkerchief to dab at the eyes while listening to his music, as one well might with his contemporaries Tchaikovsky or Dvořák, or especially his compatriot Gounod.

The thickness of textures, once unraveled, reveals a sturdy, rigorous mind, capable indeed of being touched with Romantic moments, but one who is intimately involved with the music, not with effects – perhaps that in part reflects his life-long activities as an organist and composer for the organ. Yes, he could sometimes take on the overt Romantic mantle (the symphonic poem Les Djinns is an example). In essence he is a real musician’s composer, which is why so many musicians so value his best works, such as the magnificent Symphony in D Minor (1886) or the Symphonic Variations (1888) for piano and orchestra, or the work with which de Caen ended her recital, his Sonata in A major for cello and piano.

Written in 1886, it was actually first performed as his Violin Sonata in A major, now equally well-known and equally widely performed. However, it seems that Franck originally conceived the work for either violin or cello: Eugène Ysaÿe premiered the Violin Sonata, and the cellist Jules Delsart put the finishing details to the cello version – Casals regularly performed it on his tours.

photo: Edmonton Recital Society

It is a very substantial work in four movements, making considerable demands on the cellist. The opening of this performance perfectly indicated where this interpretation was going to go: a very rich Romantic tone for de Caen, and then a real sense of quiet triumph from the piano. This prepared for the rugged interpretation that followed, avoiding any over-sentimental effects while maintaining the rich autumnal feel. Scott Hoyt is not a sentimental player – she prefers a more pragmatic approach – and this worked well here, especially at the end of the piece. De Caen concentrated on a rich tone and on bringing out that rugged lyricism.

This was not, perhaps, a performance for those who like more heightened Romantic effects – and certainly the sonata can be, and often is, played in such a fashion. Maybe de Caen could have afforded a little more anger in the second movement, and Scott Hoyt a little more bounce in the last, but this powerful performance got, I thought, to the heart of Franck’s idiom, and was very warmly received.

I actually thought that the Franck better showed off de Caen’s talent and skills than the work that was written to be a showpiece, and which ended the first half of the recital. David Popper’s Hungarian Rhapsody, written in 1893, is an unashamed attempt to compose a virtuoso piece for cello that would show off the performer’s skills, and match similar Hungarian-gipsy virtuoso show pieces for violin. Popper was himself a distinguished cellist, and he certainly achieved his aim: it is one of those pieces where the performer has to decide whether to exaggerate the kitsch, or play it down and go for a more substantial and less showy virtuosity (the violinists have the advantage here in such music, since they can exaggerate all the flourishes!). De Caen sensibly went for the latter, concentrating on tone and nailing the double-stopping.

The recital had opened with Debussy’s Cello Sonata of 1915. Both technically and emotionally this was a brave way to open the concert, and if the end of the first movement was a little edgy, this performance brought out the angular quirkiness of the music, especially in the piano.

However, I suspect that it will be for the Franck and for Rival’s new work that this recital will be remembered, not to mention how far de Caen has clearly developed as a cellist since we last heard her in Edmonton some three years ago, when she was very much just starting a public career. The wait was indeed worth it.