“He poured his soul out to all of us as we sat and listened to the story of a piano saving a life”

Review by Travis McNaught

If Darrin Hagen’s play Metronome had been about anything or anyone other than a piano and music, I don’t think it would have had such a universal and ironically human power in its storytelling. And as the stage was decorated with suspended, disassembled piano parts in a half-circle near the ceiling, it would have been pretty creepy if they tried the same with a person.

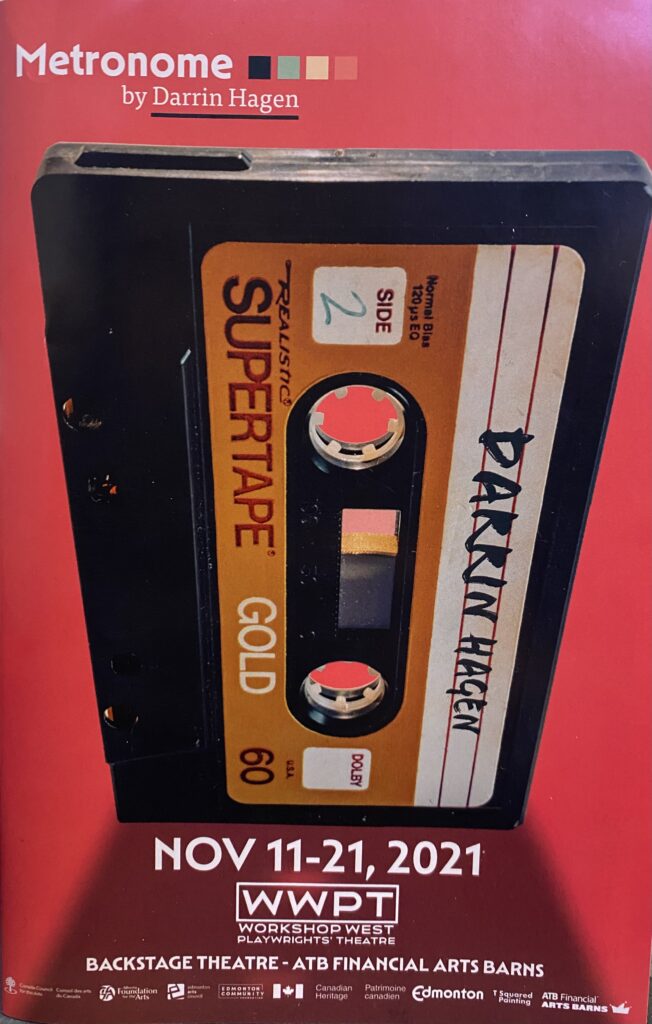

The Backstage Theatre premiered Hagen’s play on November 11, along with a post-show art shop for Crafty Neon Artwork. Seeing a new, one-person autobiographical show by Hagen was an exciting find. I knew him as the writer-in-residence for the University of Alberta, but knew he was also an impressive award-winning playwright and author here in Edmonton.

As I registered for the show earlier that day, I was pleasantly surprised by the price tier system that the Workshop West Playwrights’ Theatre had implemented during this season.

Hoping to accommodate patrons’ financial situations, they offered the admission price choice between ‘I’m doing ok’, ‘I’m doing well’, and ‘I’m doing great’ (at $25, $30, and $45 respectively). Given that I am a student who often settles with a nap for supper, you could probably guess which bracket I fell into, and it was an option that most certainly did not go unappreciated.

Finding parking was easy enough and as I’ve learned to do before, I left my car near a green ‘P’ sign and muttered a quick prayer. I know firsthand that the city is much less considerate of how its patrons are doing than the organizers of this wonderful play. Before even arriving at the doors of the theatre on November 14, I was greeted by a dishevelled stranger with a paranoid “What are you looking at, fool?”.

Ah yes, there’s that warm, inviting art scene I’ve become so fond of. At least the staff welcoming patrons inside were much more friendly.

Grabbing a programme from that charming staff and an empty seat, I realized how personal the design of the space felt. The seats were arranged in groups of one, two, or three on two connected bleachers with a few tables set up just in front of the stage for those who wished to enjoy something from the bar. I can’t necessarily give my thoughts on the bar or table experience, as I took up the same strategy for that night as I do in my classes: take a seat in the back and be quiet.

The stage’s floor was set with a circle of papers, most formed together to create a coherent center circle that wouldn’t be moved during the show, and the rest all individual sheets thrown around the edge.

In the middle was a mahogany table, a spinning wooden chair, a green tackle box, and some books and cassettes. Arguably the most important piece was the one which was often fiddled with throughout the performance: a metronome.

Every set piece was carefully placed, or suspended above the performance, with purpose by set, prop, and costume designer Beyata Hackborn. Interactions with the set pieces was a strategy Hagen clearly had a grasp of, and he often rolled the table and chair around the stage to indicate a different setting or give the audience a different perspective.

The show began with an announcement to silence all phones, walkmans, tamagotchis, and any other devices that could interrupt. During the show the speakers often played piano, recordings of Hagen’s childhood performances, and even popular music from throughout his life that added to the storytelling.

There were only one or two instances where, from my seat in the back row, I couldn’t make out one or two words in a sentence. Otherwise, the choice to have Hagen present his dialogue and stories without any harsh microphone was one which worked wonders for the personal atmosphere. Another effective set design choice was the projectors – a dramatic monologue would be matched with a single light cast on Hagen, and projectors raining white music notes down the suspended piano parts and onto the floor.

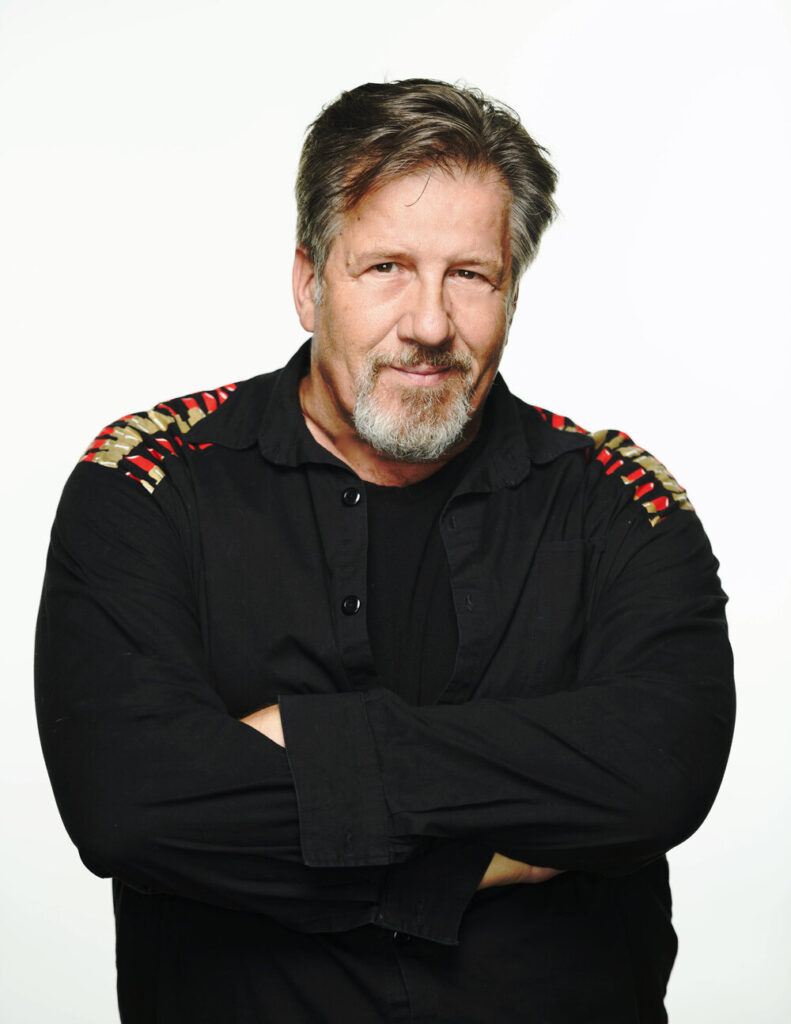

The play’s story itself is nostalgic, raw, and honest. It encompasses Hagen’s journey through life with the lens of music, specifically his Ennis & Sons piano. He connected to music at a young age and recounts the ways it grew him closer to his grandmother and parents, new friends, lovers, and to himself.

Hagen is a household name in Edmonton, and his humour and storytelling shined in Metronome. The pacing was easy to follow and flowed well because of its autobiographical nature. The atmosphere of the play created the feeling of a living room more than a large-scale performance, because of the scale and connection. We were thirty-some people in a room with one performer who felt more like an old friend telling a story. There were times when Hagen openly joked with specific audience members by name, making me feel a bit as though I was a newcomer to a special club filled with inside jokes.

The connection between performer and audience was more present than most other plays. At one point Hagen reminisced about his past jobs, detailing working at fast food chains and as a music teacher, expecting at least a chuckle.

When the audience stayed as silent as a Zoom class, he confided, “I always think that’s going to get a laugh, but it never does. Oh well, don’t give me it now, I don’t need your pity! I’m moving on, because it’s my […] show” (one word was omitted for the sake of keeping this article clean, unlike Hagen’s performance), which finally got him his genuine laughter.

At some points the audience was exactly that – a group of outsiders listening to a life story – and at others we were the second subject in a conversation. The flow of events took us smoothly through early childhood, rebellious teenage years, early adulthood, and the current day. During all of this, the piano and the theme of music was always there, both in the story and through the speakers surrounding us.

Given the nature of the play, Hagen’s emotional connection was a string almost tangibly crossing through every member of the audience. He handed it to each of us from the very first opening dramatic speech, and tugged on it when it had the greatest effect. He pulled us closer with it and kept us near enough that a breath could’ve been felt if it weren’t for the masks. Hagen’s life story and ability to tell it connected with all those who have encountered music in some way more than just by listening, but rather by feeling. And in all honesty, I think that was every single member of the audience in the room with me that night.

Nearing the end of the story, one could hear what sounded like a knot in Hagen’s throat, an unexpected but appropriate overwhelming of emotions. As the story moved forward, we learned of the countless hours Hagen spent with his piano, and of the relationships in his life which were strengthened, changed, or reconciled because of the instrument. Many years ago, Hagen felt a sense of conviction and acceptance that the piano had done for him what it needed to, and decided to let it do the same for another young member of his family. He had poured his soul out to all of us as we sat and listened to the story of a piano saving a life, and we each let out a sigh of sorrowful acceptance that the piano had since moved on to save another. Perhaps I can only speak for myself, but the climactic ending was an emotional payoff which earned a tear or two along with the collective sigh.

Leaving the theatre was difficult, as I could have stayed in the space and enjoyed the set for many more hours. The show ran for almost exactly 90 minutes, and as I walked towards where I had parked, I overheard an older couple talking about how much they enjoyed the experience.

I silently agreed with them and as I got to my car, I celebrated the empty windshield boasting no paper tickets. Thoughts of my own interactions with music, and images of my guitar gifted to me by my grandfather began to fill my mind.

The short drive home was one which allowed for a bit of this reflection, but I mostly focused on the sounds of my favourite piano album playing through my car speakers.