Review and photos by Rachel Papulkas

The Edmonton International Film Festival is an annual event that celebrates artistic creations of filmmakers from around the world and hosts a wide selection of films in the heart of the Canadian Prairies. Running this year from October 1 to the 10, the EIFF is a space for both filmmakers and filmgoers to engage with a variety of different films, from live action comedic shorts to insightful documentaries. The mission of the festival is, by their own words, “to encourage and support the appreciation of cinema.”

Having appreciated cinema from the comfort of my own home with a handy Netflix subscription, hearing of the festival made me realize how much I missed the shared experience of watching a film inside a real theater. After looking through the online schedule, I decided to treat myself that Monday afternoon. For a small fee of $10, I was to watch a collection of six short documentaries, all under the vague descriptor and overarching theme of life under systems greater than us.

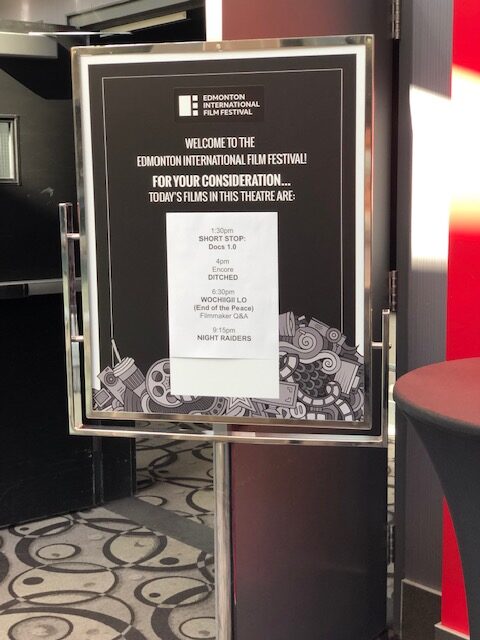

Arriving at City Centre, and making my way up to Landmark Cinemas, I walked across the checkered tile floor, I was immediately greeted with the classic cinema letter-board: “RIGHT HERE AT LANDMARK CINEMAS: OCTOBER 1-10: EDMONTON FILM FEST.” Looking upon the posters highlighting some of the featured films of the festival, I was happy to also see the signs warning of the required proof of vaccination, as also advertised on their website.

Inside the actual lobby, EIFF presence was light. A big black booth just beyond ticket checks was manned by three jovial EIFF volunteers. Just around the corner from their booth was a rather lonely looking red-carpet, complete with a EIFF photo backdrop. As I walked around the lobby, killing some time by purchasing some candy, I didn’t catch anyone using the backdrop. It was a nice detail, one that I imagine was a bigger hit for the later showings including actor and filmmaker Q&As. Not so much for the Monday 12:15 showings frequented by one tired university student, and the two other elderly ladies waiting to go in with me to the theater.

About ten minutes before show-time, I followed the dimly-lit passageway and the bass thumps of the pop music playing within Theater One, my eyes immediately catching on the colourful animations looping on the big screen.

Finding my pre-bought seat at the back of the auditorium, I paid closer attention to the messages on the screen. Putting together an internationally recognized festival is hardly a one-person feat, as reflected by the list of acknowledged sponsors, but I was pleasantly surprised by the easygoing, comical tone of the messages. “It’s really good to see you. That mask brings out your eyes”, “Air hugs and elbow bumps to our sponsors”, and “This message loops often, don’t let it make you loopy” were among the messages, along with animated sun and flower imagery. Or, at least, me and the (now three) other people in the theater found them funny. We shared a good chuckle for the first two loops of the messages.

Just underneath the screen sat four director’s chairs and accompanying microphones. While I did not know much about what films I was about to watch, I did know that it was one scheduled event that did not include a filmmaker Q&A. I felt disappointed that I wasn’t going to have the opportunity to ask the filmmakers questions about their process. After a quick introduction by an eager festival volunteer to open the show, a half-serious attempt to do the wave, and a more serious acknowledgement of Treaty 6 territory, I settled in with my nearly empty bag of candy to finally start the show.

The first of six documentaries was emotionally lightest of the bunch. Home, directed by Mahmut Akay, is a six-minute documentary following the life of celebrity hairstylist Adem Oygur, and his mission to never stray too far from his roots back in the village of Divaniturk. Oygur’s voice narrates his upbringing in his home village, a close-knit community of hazelnut farmers that were reluctant to let him pursue his dreams of becoming a hair stylist. While the film shows the excitement of Oygur’s career-defining moments, it was the warmth exuding from the footage of his loved ones back home that I felt most of all. The community of Divaniturk was just as much a main character as Oygur was, shown by the editor’s choice to show just as much of the family and friends that raised him as they did Oygur himself. The film was a sweet beginning to my afternoon, but the exclusion of how Oygur coped with an intense shift of lifestyle makes me think that a sweet film missed the opportunity to also be impactful.

The Long Today, directed by Niobe Thompson, was another featured film that followed in the same vein of cherishing your roots. Initially pitching itself to the audience as just another father-son canoeing trip taken by Niobe and his father, The Long Today unfolds as one twenty-minute love letter to the relationship between a father and son.

Niobe’s father, celebrating his seventieth birthday, is a comical individual who merely shrugs at the idea of tackling the dangerous waters with an old wooden canoe, and swears by the philosophy of never living too far into the future. The film is narrated by an adult Niobe, a chronic worrier and overthinker. Filled with shots of their adventures in the woods, the film reflects mortality and the realization I make alongside Niobe: that there is no guarantee of ‘a next time.’ It’s a bittersweet acknowledgement that made me think of my own close relationship with my father, and the discomfort that comes with watching him age. The Long Today was a sweet interlude in the event’s programming before moving onto heavier topics.

One such film that weighed down the theater with its implications was that of Maalbeek, an animated short stylized with 19th century Pointillism directed by Ismaël Joffroy Chandoutis. Sepia-toned images of subway carts, echoes of footsteps and chatter, followed by news reports and saved voicemails help tell the story of Sabine Borgignons.

Sabine is an amnesiac survivor of the 2016 Maalbeek metro station terrorist attack, and after waking up from a three-month coma, Maalbeek is her stream of consciousness in trying to piece together what happened that day. Sabine struggles to remember a day that everyone else seems to, such as the first-responder who found her, and the friend who wishes she could forget like Sabine did.

Aesthetically, the Pointillism technique effectively conveyed the concept of a fractured memory that Sabine is attempting to piece together. I felt like I was being taken on the journey with Sabine, attempting to reach a conclusion together that was slowly forming over time. One aspect I deeply appreciated was the focus on Sabine herself. Instead of spotlighting the perpetrators, the filmmakers kept the focus narrowly on Sabine and her experience. Sabine was telling her story, as uncertain as she was, and it made Maalbeek a standout in the collection of films that afternoon.

Life’s a Bitch, likewise, took the animated approach in storytelling, a sketched aesthetic devoid of colours other than black and white, with the rare pop of red. Varya Yakovleva’s six-minute short features one long day in the life of a man who made a home out of a bench in a subway station. Owning only one blanket to keep him warm, the man speaks of society’s rejection of him after his foot amputation deemed him unemployable. It’s an emotional 6-minutes, in which the man is repeatedly ignored.

Greetings from Myanmar, directed by Andreas Riiser and Sunniva Sundby followed shortly after, its emotional punch delivered by the contrasting shots of a peaceful Myanmar hotel and the audio testimonies of victims of the Rohingya ethnic genocide occurring only 10 kilometers away. While tourists enjoy a relaxing vacation laying poolside, toasting drinks over well-prepared food, Muslim Rohingya men and women share their traumatic experiences of being forced to flee from their homes to escape torture and persecution by the Myanmar military. It’s an unsettling film, making me sit in my own discomfort at not knowing much about the tragedies talked on-screen.

The Box and The Time We Have Left capped off the showing. The Box, directed by Shal Ngo and James Burns, centers its narrative around three individuals who have spent a collective nine years within solitary confinement: Five, Pam, and James Burns himself. Exploring the cruelty behind social isolation and its psychological impacts on its victims, The Box features a mixture of stop-motion animation and dramatized scenes to tell the narrators’ stories. The film is shocking, educational, and is a testament to the importance of human empathy and connection.

The Time We Have Left, directed by Blake McWilliam and Niobe Thompson, concluding the event, is a call to action for the climate crisis—the filmmakers are angry and impatient at the willful ignorance of global warming. Appropriately beginning and ending the film with Greta Thunberg’s United Nations speech in which she states that “climate change is coming whether we like it or not”, the film educates the audience on some historical reactions and resistance to climate change, the planetary tipping point, and hothouse earth. The short is structured to flash back and forth between discussions from climatologists, and dramatizations of what those consequences will look like in the future.

While I found some of the acting stiff, it was impossible for me to miss the similarities between the vignettes and the real wildfires and floods I hear about on a frequent basis.

With the conclusion of six powerful short documentaries, it is no wonder that all of us within the theatre remained quietly seated even as the lights slowly turned on. I wondered if they were weighted down by the same thoughtfulness I was experiencing. Rising from my seat, I couldn’t help but overhear two of the ladies I’d entered the theatre with.

“They made fun of her, you know. The young girl.” One of the women spoke, leaning down to grab her jacket. “For wanting to make a difference and telling us that we can too. And they just made fun of her. But did you hear all that?”

Walking with the two women out of the theater, I thought of those words, and how they reflected, at least in part, everything that I’d watched that afternoon; the reflection of the parts we all played in systems larger than just ourselves, or changes we wanted to see in the world. In 80 minutes of film, I was exposed to six stories, some of which covering topics I’d never heard much about before, and left feeling a bit more of that appreciation for storytelling that the EIFF strives for.

Edmonton International Film Festival website

See also Hands That Bind: movie review