Many years ago, or so the legend of la chasse-galerie has it, the Devil made a deal with an industrious hunter…

review by Trista Peterson, photos by Yvonne Peterson.

Many years ago, or so the legend of la chasse-galerie has it, the Devil made a deal with an industrious hunter: attend Sunday mass, or be damned to an eternity of roaming the night sky in a flying canoe. So enthralled with the Saturday night hunt, he missed his weekly worship.

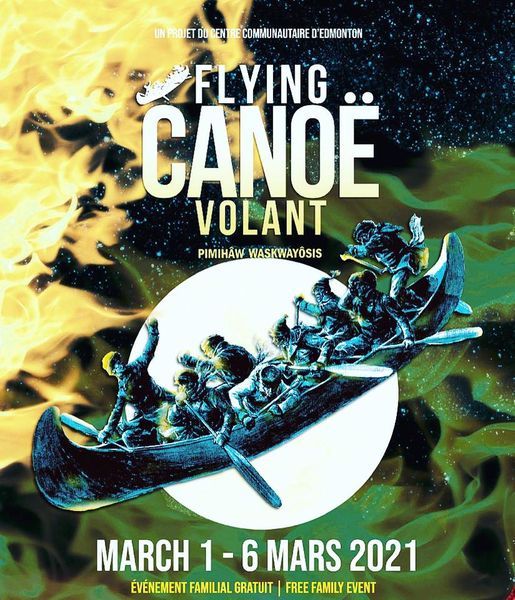

Edmonton’s magical Flying Canoë Volant festival resurrects the tale of his unfortunate fate, and against all odds, it returned this March– albeit without all the magic.

Combining French mythology with Métis and First Nations traditions, the Flying Canoë Volant festival is located in both the heart of Edmonton’s French quarter (86 avenue and 91 street) and the nearby Millcreek ravine. Combining French mythology with Métis and First Nations traditions, it transforms the dark woods into a spectacle worthy of its supernatural inspiration.

Projected twirls and patterns of multicoloured lights dance along the frozen ground and lamps hanging from tree branches illuminate the woods. Mythical creatures (or rather, volunteers in creative costumes) pace the trails. Wolves with electric-red eyes howl as they pass, and elfin figures with long white curls patrols the grounds.

It’s the perfect otherworldly, mystical antidote to a cold and drab winter evening.

In a regular year, people are free to come and go as they please, but, in compliance with COVID-19 safety protocols, there was a strict cap on attendance. Pre-booking was necessary, and luckily my mom (who is much more on top of these things than I am) managed to snag us an 8 pm spot on Thursday (March 4th). She and my dad had made the six-hour trip from north of Edmonton. First-time Flying Canoë Volant festival-goers, they were eager to see what I had so enthusiastically described to them the year before.

Due to the reduced attendance, parking was a breeze – we immediately found a spot on a nearby residential street. I pulled a faded cotton mask from my pocket (one of probably 40 reusable masks I’ve collected over the last year) and grabbed a coffee from Café Bicyclette, a cute little coffee shop located in the French Quarter right across from the festivals’ entrance. My parents followed suit, and we were off.

Once inside the festival grounds, the difference from last year really hit me. Where there was a covered stage on which live bands played lively tracks for dancing festival-goers, there was now a somewhat muted display of local art, mounted on wooden signboards a little taller than me. Lovely as the paintings were, they didn’t really grab our attention, and the silence only amplified the lack of festival cheer.

There were, however, some really well-done sculptures beyond the signboards. We paused for a few minutes here while my mom (the shutterbug that she is) took photos. Featured among them were what looked like a Scotch tape polar bear and a frankly adorable nest of illuminated “unicorn babies.”

My favourite, by far, was a gravity-defying canoer (our ill-fated hunter, perhaps?) suspended among laser beam-like threads.

From there, we started the downhill trek toward the ravine. A combination of melting snow and the evening chill made the journey down the rather steep road feel more like a Red Bull-sponsored downhill ice skating event. Diligent volunteers in red caps scattered the treacherous terrain with salt, keeping us from experiencing any major slips.

We found that the trails in and around the ravine were carefully marked into a one-way only route that guided the flow of (reduced) foot traffic along the festivals’ attractions. Like the one-way walking rules in West Ed, this is a remnant of COVID-19 I wouldn’t mind seeing stick around. Not worrying about bumping shoulders with oncoming traffic, or missing a part of the event due to taking the wrong path, actually made the experience more pleasant.

The first of the attractions along the path was the First Nations village. Several teepees, brightly painted and illuminated from within, stood in jarring contrast to the dark of the sky above.

It was beautiful, but again, too quiet. Last year, I was utterly moved by an Indigenous round dance taking place around a blazing fire in the First Nations village. Festival-goers were invited to join in, taking the hands of friends and strangers alike, and learning to step to the beat of traditional Indigenous drum music. It resonated from all around like an ethereal, earthly heart beat.

This year, two large screens showed projections of performances by Indigenous musicians, most notably Alberta’s own Juno-winning singer-songwriter Celeigh Cardinal. I enjoyed the videos and their display of excellent Indigenous music, but I felt that now-familiar pang of things not being as they should be. Maybe it was our near-year of isolation, but I craved the experience of joining hands with strangers more than ever.

My parents, not having any past versions of the festival with which to compare, loved the teepees. Painted messages urging unity, understanding, and love covered part of one teepee, which we stopped to read before moving on.

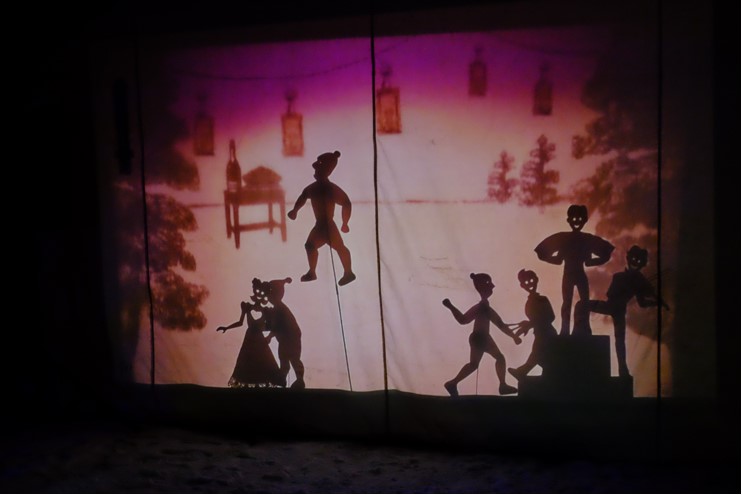

The winding trail along the ravine took us to the next exhibit – the Trappers Cabin. Here we found a tent onto which a short, seven-minute film was projected which, to our delight, portrayed a creative spin on la chasse-galerie. Since it was a relatively temperate evening, we stopped and watched.

The film employed a projector and hand-cut paper figures, manipulated by sticks, to tell the story of three hunters warned by the Devil to make it back to work the next morning on time, or else! Though the galivanting protagonists were nearly tempted by women and mischief to stay out all night, they managed to make good on their end of the deal, much to the Devil’s dismay.

The short film was clever and fun, but despite the mild weather, my cold toes were relieved to get moving again, once “FIN” was projected across the screen.

Last, we stopped by the Métis Settlement. Last year, live music blasted from a small tent and guests were invited to step up onto a small dance floor and learn a Métis-style jig. People cooked bannock (a delicious, Indigenous-style fried dough) over the fire and could dip into tents to warm up.

Though I didn’t partake in the dancing (probably not wanting to trip over my own feet in front of the crowd), watching strangers dance with one another, laughing and singing along to the music, was a personal highlight. Of course, none of this was possible this year. Instead, a projector and speakers cast music videos across a large screen – similar to those in the First Nations Village.

Scratch that – they were exactly the same songs as the First Nations village. I counted four songs (though in all fairness, it may have been more – but not much more). The festival volunteers must have been dying to pull the plug on the whole speaker system after the tenth, fiftieth, hundredth playthrough of this ultrashort playlist. Couldn’t they have found more music? With Celeigh Cardinal’s “When All is Said and Done” playing yet again, we started the final leg of the trail.

From here, the illuminations on the ravine paths became truly spectacular, resurrecting the sense of wonder and community that I had been really missing only moments before. Kaleidoscope-like projections of lights cloaked the path, and neon displays hung from the branches were brighter and in greater numbers than any other part of the trail.

My mom pulled her camera out again, ordering us to pose and shouting directions like a Hollywood director.

“Act like you’re looking at the lights!”

“Stand in front of that tree!”

“Look up at the lantern!”

We obliged, though none of the photos turned out with it being so dark. I even took a few myself, you know, for the ‘Gram.

Others stopped, like us, to take pictures and marvel at the light displays. I realized at that moment how much I loved just being around people, even from a distance. I liked seeing couples pose for pictures. I got a kick out of watching kids bundled up tight in snowsuits clumsily chasing the flashing lights. For a second, it felt like any other year. We took the stairs back up to the top of the ravine, and called it a night.

Without the live music, food, and general cheer, Flying Canoë Volant certainly had lost some of its signature magic. But I commend its organizers for the amount of wonder that they were able to preserve, given the wildly unpredictable and challenging circumstances.

It remained a lovely evening out, showing my parents Edmonton’s abundant river valley trails and a small part of the city’s famous festival culture. Did I miss the music, the food, the dancing? Yes. Am I glad I came out anyway? Absolutely. Next time – and there will be a next time– I won’t miss my opportunity to make a fool of myself on the dance floor.

Flying Canoë Volant took place from March 1-6, 2021.