“At the entrance, depraved higher vibrations burst through the opening door, teasing us to enter…”

by Joshua Nhan

It is midnight as we exit the Uber. Dressed in animal prints, furs and feathers, we sharply contrast the bleak backdrop of the light industrial area in south side Edmonton. The address to the Transient is received by text message the day of the rave, along with a reminder of the venue’s safer spaces policies. Those wanting an invite must have someone post their names to the private event page on Facebook, allowing for a brief screening before being accepted.

We follow a metronomic thumping of bass, passing one identical door after another as the low, muffled sound crescendos with each step. At the entrance, depraved higher vibrations burst through the opening door, teasing us to enter.

After being identified on the guest list, we proceed to a bar offering a simple selection of Pabst Blue Ribbon, classic highballs and bottled water. A self-serve station is set up nearby with filtered tap water for refills. With drinks in hand and plug in our ears, we continue our path to the speakers and soon find ourselves facing a large, crowded dance floor. The air is warm and humid with perspiration from the crowd looking up to a DJ, barely visible on the second floor.

Mesmerizing fractal patterns are projected on the walls, twisting and inverting its angles, choreographed to the music. Oscillating beams from strobe lights and lasers solidify upon contact with artificial fog, dilating pupils in a hypnotized gaze. Pieces by Edmonton artists are hung from ceilings and walls. At one Transient that featured ambient music, the floor was lined with fresh sod so guests could lay in comfort and become immersed in the projected visuals and droning musical vibrations.

A driving 130 BPM kick drum falls on each quarter note of a 4/4 time signature. A vocal sample is cut and used in a percussive staccato between each kick, while a synthesizer becomes a mantra, casting a spell on the listener. A crisp hi-hat is introduced, hit loose on the offbeat, and soon afterwards, a clap is added on the second, and fourth. Computerized sounds and samples are tweaked and panned, brought to life and manipulated around the room in mystical forces. While the tempo remains constant, the DJ seamlessly adds and subtracts instrumentation at will, creating a dizzying effect by dropping sound frequencies and turning them around.

The DJ tactfully and slowly withdraws, leaving only the original kick drum with minimal accompaniment. The crowd becomes anxious as the maestro begins building anticipation, slowly picking up energy, then resting climatically on the edge. I see faces in the crowd contort like that of a soloing musician as they become overwhelmed by the tension. Suddenly, to the crowd’s relief, the DJ opens the floodgates of sound and the party resumes.

People transform on the dance floor, shattering their inhibitions. Heart rates climb to match the tempo. Limbs grow minds of their own. Arms pulsate independently from footwork that has awoken from a dormant subconscious. The linguistics of dance and movement take prevalence, as a hundred people become engaged in a dialogue put forth by the DJ. Dancing in a group, or alone, there is no better way to feel a connection with others. Without missing a beat, I use my sleeve to wipe the sweat stinging my eyes and become drunk with music. The surrounding lights provide an added stimulant.

At Transient, smokers do not need to fear a no re-entry policy. The back door leads to the designated smoking area, sectioned off in the parking lot of the U shaped complex. The complex becomes vacant on the weekends, while the shape provides a secluded space hidden out of sight. Many non-smokers take advantage of this for a breath of fresh air and unstrained conversation, to pace out the party that runs until 7 AM.

Hiding the DJ’s stage represents the guiding principle of Refuge, the organizers of the event. Placing the importance on sound quality and music, even world famous DJs are put second to their art. As Edmonton’s only true source to underground dance music, Refuge prioritizes music and sound over commercial practices and the legal rigidities of the industry.

“The main concept, for Refuge, is long sets, eight hour parties, and good sound.” says TAF, a member of the crew. He explains how Refuge was formed in 2012 to counter a “really shitty era of Edmonton dance music.” He refers to a “plethora of venues and clubs playing cheesy pop,” as a symptom of the lack of investment in proper dance culture. TAF admits that Edmonton, limited by its size, may “never compare to any major city in terms of the infrastructure.”

2 AM last call compels late night businesses into a race for revenue. To bring in customers, nightclubs often overbooked local DJs hoping to draw out as many of each clique as possible. At times, this restricted set lengths to only half an hour, something unacceptable for Refuge.

“If it’s too commercial, you lose the history, you lose the authenticity and it becomes a parody of itself. It becomes about money. It disregards the people that made the industry happen. The proper respect of history is such a huge part of a proper dance music scene”

TAF pays homage to “New York, Chicago and Detroit, the magic triangle of dance music. Disco came from New York, house from Chicago, and techno from Detroit.”

He credits David Mancuso as a pioneer of the invite-only, underground party concept. In 1970, David Mancuso began hosting the exclusive party that became known as The Loft. In a 2003 interview for discomusic.com, Mancuso reveals how moving to a “neighbourhood that was mainly comprised of factories and warehouses,” and an interest in high-end sound equipment set the conditions for the first illegal raves.

The Loft became the institution for New York disco, and the invite-only policy made it a safe haven for coloured and queer communities that faced discrimination during the HIV epidemic. The Guardian claims that “the crowd of Mancuso’s parties drew were pansexual and racially mixed- about 60% are black and %70 are gay, according to one estimate- a gathering of the disaffected and disenfranchised.”

Out Front Magazine reveals the, often forgotten, queer history of dance music in Chicago and Detroit, exposing the common misconception that the “genres of house, techno, drum ‘n’ bass, electro and many other sub-genres… were created by white, European men in the early-to-mid 2000s.”

In Chicago, The Warehouse opened as a private nightclub in 1977, hiring resident DJ, father of house music, and protégé of Mancuso, Frankie Knuckles. Like The Loft in New York, The Warehouse became a popular space for gay, Black and Latino communities, especially before the city adopted its first anti-discrimination law, The Human Rights Ordinance, in 1988.

In Detroit, “white flight” suburbanization and the loss of industry as a result of mechanization beginning in the 50s, resulted in racial tensions and an impoverished inner city. Embracing these themes, techno took “sound further into the stratosphere with a harsh, hardcore sound full of riffs and industrial bleakness.” Detroit techno originated from suburban black folks, using music to create an identity for themselves beyond an urban, “essentialized blackness.”

For TAF, “the Black and queer scene is so important in dance music. It’s something lost in contemporary dance music. It takes time to be exposed to that and [he hoped] that the Transient fast tracked that, and gave that window to people.

“We used to have a really strong techno scene, warehouse parties used to be a big thing in Edmonton. We have a legacy of really good DJs.”

He refers to underground legends Rob Tryptomene and Dane, who ran Treehouse Records until 2014, a staple for TAF’s vinyl inquisitions.

Tryptomene released multiple records in the early 2000s with success in the UK. He eventually stepped away from music, becoming part owner of The Common, a popular downtown gastrolounge, hiring Dane as the resident DJ.

Dane has built an illustrious resume, having played in world class venues in Europe and North America. As early trailblazers and contributors to Edmonton’s dance culture, both names carry heavy weight at Canadian electronic music festivals, like Shambhala and Bass Coast.

A 1993 article in the Edmonton Journal described a rave at Nix, a 300-capacity, private warehouse now occupied by Parlour Italian Kitchen & Bar. The reporter describes the ravers as “university kids, trendies from the alternative and gay scene, [and] clothing and record store groupies.”

Posters advertising Edmonton raves provide an archive of evidence for the city’s once thriving dance scene. Addresses listed direct us to buildings now recognized as The Starlite Room, The Mercer Building, The Yardbird Suite, Room at the Top and the Polish Hall, to name a few.

The Edmonton Journal reported a “series of late night tours” taken by Mayor Bill Smith in 2001, to observe the activities of the city’s after-hours. Later that month, Smith signed a bill banning all night events for people under 18, causing protest at City Hall. At another rally, The Globe and Mail describes “techno [being] pounded outside the Alberta Legislature as where about 150 young people gathered to dance in protest of growing regulation on raves.”

“There was no way we were gonna be a legitimate promoter in clubs. We developed an image of being outside of the clubs.”

Being “schooled” while on a foreign exchange program, TAF returned well-versed in the extended nightlife of Europe and was committed to create something similar at home. For Refuge, dance music must take you on a journey, “dancing for eight hours at a time,” for it to be truly understood. Realizing clubs were not going to let them play music the way they wanted, they carved themselves a niche outside of the norm.

TAF adapted to the circumstance. Resourcefulness led him on a hunt to different city parks, scoping the area and testing power outlets. Eventually, he found a suitable spot in Hawrelak Park to power the equipment, and the soon-to-be Refuge crew hauled in and set up. In 2011, they held the first impromptu “renegade” party, playing for families passing by.

Naturally, noise complaints had them kicked off the grounds and forced them to relocate. The next year they found “the perfect outdoor dance venue” in the river valley, near Louise Mckinney Riverfront Park, in downtown Edmonton. Officially branding the event as Refuge in the Valley, they were granted a facility rental license, permitting the party to go as late as 11 PM. The free all day event began picking up momentum with a presence on social media, and Refuge had applied for a liquor license. In 2015, their operation was shut down due to construction of the LRT Valley Line Southeast.

Meanwhile, Refuge had also been throwing raves at an unlicensed venue on Calgary Trail, inspired by, and the namesake of Mancuso’s Loft. Operating from 2013 to 2016, Edmonton’s version of The Loft was less of a venue and more of a hang out. TAF remembers the raves held there being highly disorganized and untidy, eventually being the reason they stopped throwing parties there. TAF admits that “the loft was fun, but never perfect. Refuge was always looking for perfection. Before Transient, the closest we could get was the River Valley.”

Other Edmonton based promoters were booking clubs and venues, so Refuge “developed an image of being outside of the clubs” and focused their efforts at creating an underground, where they could control every aspect.

“The first couple months of that summer camping out in random industrial areas. Every Saturday, I would go out to an industrial area and look for leases, if I saw anything I liked, I would go out in the middle of the night and sit there, to see what was happening in the area.”

The lease to the Transient warehouse was signed in 2016. Finding the perfect space required considering size, location, evening activity of the area, and possible issues with neighbours and police. Refuge turned down a promising space after learning it was adjacent to a taxi company, foreseeing conflicts coming from bleeding sound. To the landlord, who only ever required the rent cheque, the Transient was guised as an arts and music studio.

“It was like, boom, literally everything there was already in my head. I already knew where everything was going to go. And the upper floor, that’s what made it,” TAF describes his eureka moment with the warehouse. At a later Transient, he learned from a guest that the same location had been used for raves in the past.

The first Transient was held on October 31, 2016, with just a third of the 180 capacity in attendance. Booking New York DJ, UMFANG, on New Years Eve, TAF describes the first show where he “had a sweat… [They] cleared 220 people that night” before realizing “that’s how these spaces get busted.”

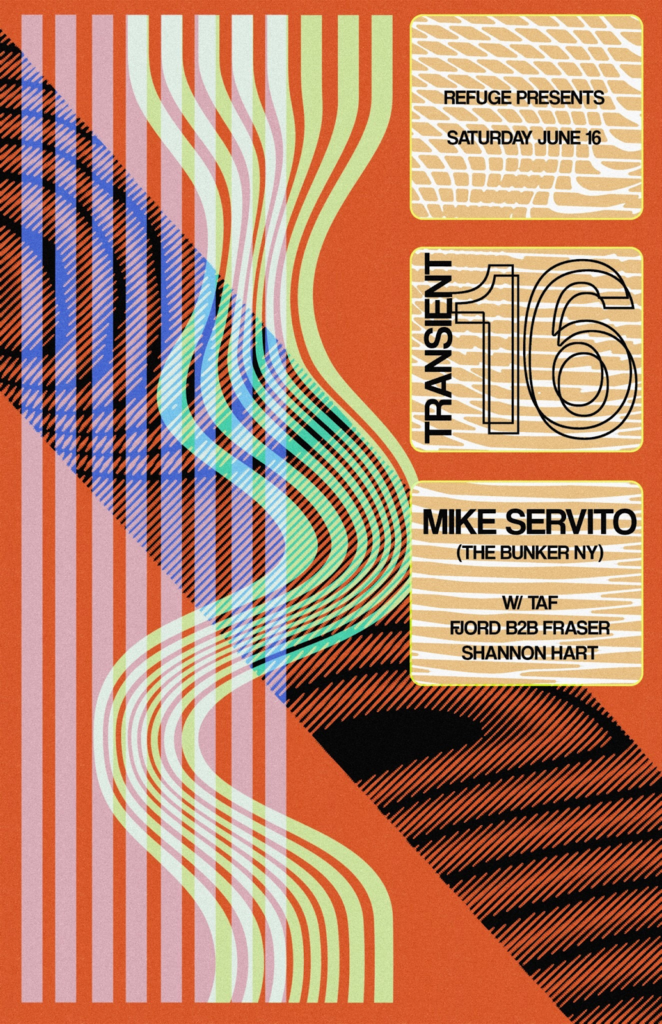

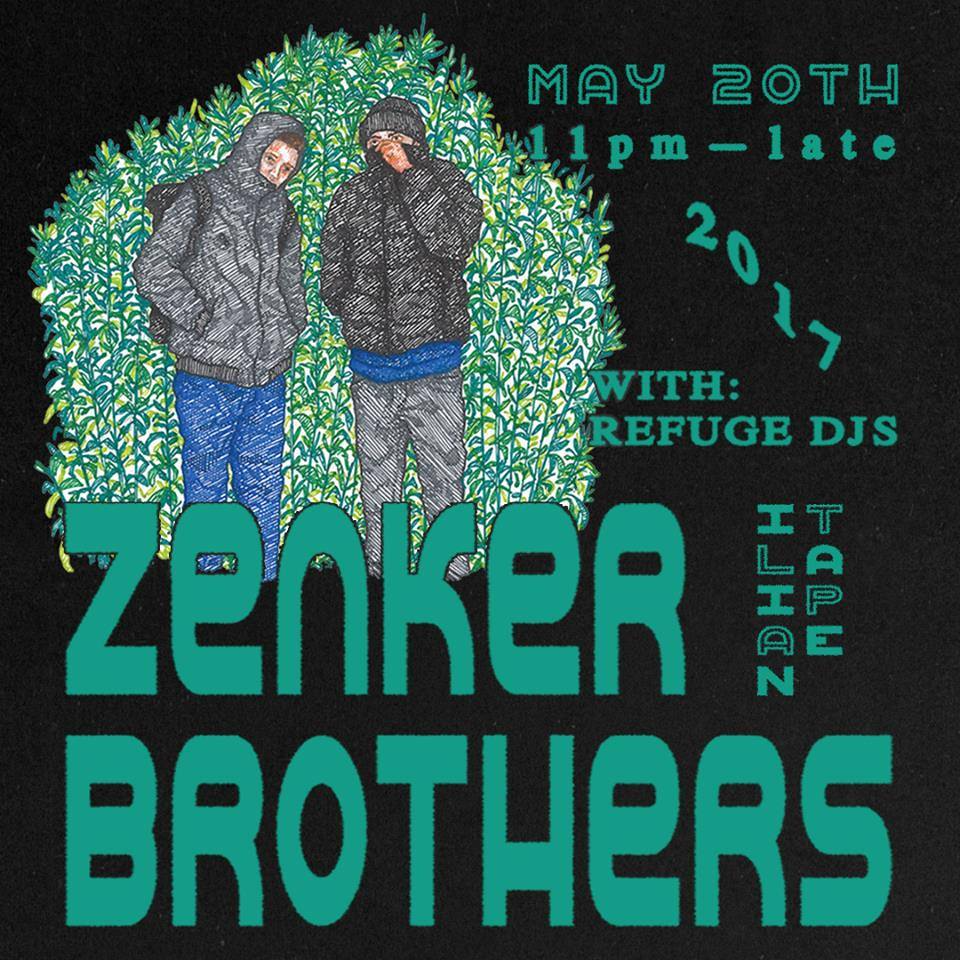

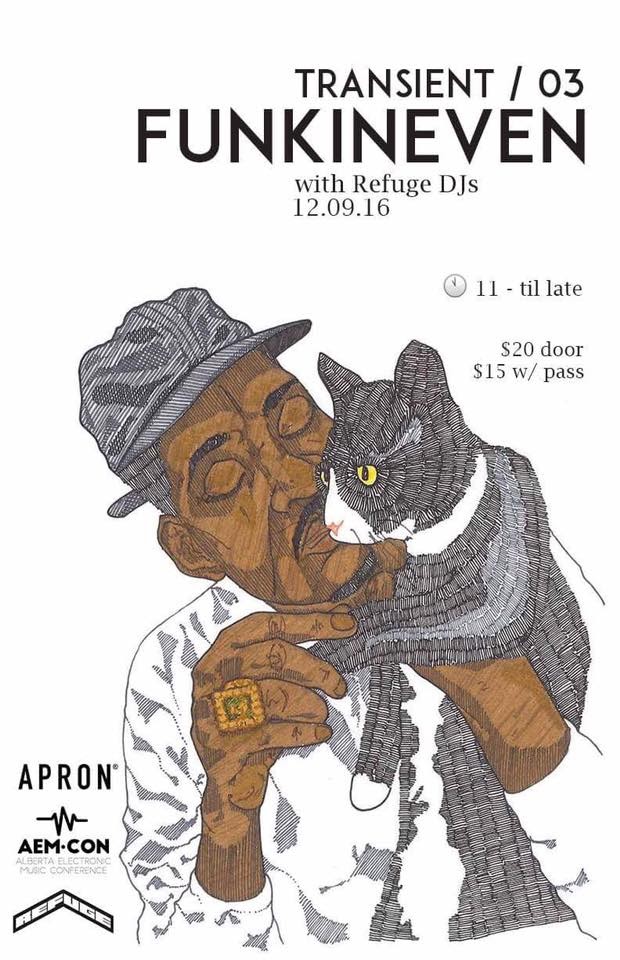

In the following three years, Refuge would host almost 50 more raves, booking international acts like Wajeed, K-hand and Mike Servito from Detroit, Zenker Brothers from Germany and FunkinEven from the UK. Refuge also worked closely with other organizations in Edmonton, booking local DJs to support headliners. Many of these DJs’ “specialty is playing three hour sets,” making the Transient the only viable venue in Edmonton for underground artists.

“Club culture, especially in Edmonton, is binge culture, making it inherently less safe. You could get really fucked up at Transient, but burn all that energy off by 7 in the morning, so that way, it’s almost safer for you, because you have people watching over you the whole time. You have access to water, and you don’t get sent home in a cab fucked up with no one to take care of you.”

For Refuge, the “worst case scenario was jail. If someone dies in the venue, that’s a serious issue, but in a way, it forced [us] to do things that made Transient safer. Having policies in place to deal with sexual assault, racism or misogyny.”

From monitoring the level of sound, to abiding by building codes, to employing harm reduction staff, TAF jokes that “it’s kinda funny how the illegality of it is what made it safer.”

“The majority of the time, it’s getting totally trashed. You go out to the bar at 11, get wasted and then get kicked out at two,” TAF describes Edmonton nightlife. At the club, someone appearing too drunk will be escorted out, left vulnerable and disoriented to fend for themselves. Alcohol and cocaine, known to make users aggressive, are heavily consumed in bars and nightclubs. Reports and statistics of violence in these establishments tell us that a venue’s legality does not make it safer. Likewise, getting caught having or using recreational drugs at a club will land you on the curb, or worse, in the back of a cop car.

The reality is that drugs are being taken in pubs, bars, nightclubs and raves. However, taking recreational drugs “in a club, you have to hide somewhere and that is not safe because people don’t know about it.” The worry is that a shroud of secrecy could hinder, or even prevent help, in the case of an emergency.

TAF agrees that recreational drug use “is a part of dance music, but if you get into it with the focus on partying and drugs, you don’t learn the culture. If you want to get fucked up, you can feel safe about it, you can enjoy it and people won’t judge you. If you don’t want to do drugs, the music drives the experience itself.”

Refuge credits Edmonton’s Connect crew for their safer spaces policies, aimed to “create a supportive and non-threatening environment.” This is to ensure there are procedures in place for how to react in situations of discrimination or assault, and to encourage attendees to respect, and protect, one another.

“Transient filled such an important niche in the dance music ecosystem. And now that’s gone.”

The final Transient was held on August 31, 2019 with 221 people in attendance according to Facebook. TAF admits the endeavour was a costly expense, but he has no regrets. But in today’s COVID-19 pandemic, TAF adamantly believes “there is no reason to be throwing underground parties, because even normal venues are suffering.” Refuge will not be organizing any parties until it is safe to do so.

John-Paul McVea has compiled an extensive archive of Edmonton rave memorabilia in his E-town Rave History Project. His blog includes a vast collection of rave posters and hundreds of newspaper articles, reporting on raves within the Edmonton scope.