“I can finally tell in public the story that I’ve been telling always”

interview by Annie Wildemann

“History would be better remembered if it was told in stories.” Rudyard Kipling

Growing up in Edmonton with a single mom, Amber Paquette did not have a lot of connection to her extended family. She knew that she was Metis; however, because of the dissonance between herself and her family, she felt that the Indigenous knowledges of her ancestors had not carried over to her generation. Desperate to know her family’s legacy, she started to read books Indigenous history in Alberta.

Amber knew from her mom that many places in Alberta were named after her Iroquois, Cree, and Haudenosaunee ancestors. For example, the Yellowhead Highway and Jasper both bear their such Indigenous names. However, the personal significance of these names did not sink in until she saw them in print.

“Understanding the stories and people behind the names of a place helps develop the context of that place. In turn, these places no longer become objective,” she says. “They become intimate places that have a deep contextual meaning. They help create a new personal cosmology.”

Quickly, history became her passion.

“Fittingly,” Keith Gerien says in his Edmonton Journal article about Amber, “she now works as a Fort Edmonton Park interpreter. Some days she plays the daughter of Fort Edmonton’s ‘chief factor’ John Rowand, while other times she dons the role of one of the countless First Nations and Metis women whose labor made the fort tick.”

This role enables her to finally interact with her history, as well as with others who live in Edmonton.

That being said, Amber Paquette never planned on becoming a historian – let alone Edmonton’s first Indigenous Historian Laureate. “It kind of just happened by accident,” she says, laughing.

But it “means the world”.

“I imagine,” I reply, “it is crucial for minority groups to have a platform to speak about issues”.

“I can finally tell in public the story [of Indigenous people] that I’ve been telling always”.

It is clear from talking to her and hearing the joy in her voice, that Amber is incredibly passionate about Indigenous stories. For her, even though they happened in the past, these stories are an extension of herself. This love permeates the work that she does as Historian Laureate. She recounts how she became Edmonton’s current Historian Laureate to me over Google Meets.

“I was approached by Robin Wallace [the reference archivist for the Provincial Archives of Alberta] after a short film that I had created [about the Michel people of Canada] was shown at the Citadel Theatre and he told me that I should apply for this position.”

“Had you heard about it before?” I asked.

She said that she had heard about the role from the ‘Let’s Find Out’ podcast, but she didn’t know much about it.

“I applied last minute,” she tells me, and “things have just snowballed from there”.

In addition to history, Amber is super passionate about art, specifically, film making and poetry. For her, art and history are conduits because together they can both help people to better understand difficult historical concepts. Through her work as the Historian Laureate, Amber has noticed that Edmontonians really like photographs. They are an “excellent way to keep them engaged”.

Currently, Amber is working on a book of poetry that she hopes to publish next year. She also is planning on making a series of short, documentary films that focus on local stories and people. Amber says that she hopes to incorporate photographs taken by the late James Brady in this series.

Brady, one of her personal heroes, was the founder of the Metis Association of Alberta, a great leader, and a passionate photographer who chose to use his talents to take thousands of photos of the everyday lives of Indigenous people during the early 20th century.

He spent his life traveling between Alberta and Saskatchewan, engaging in political activism centering around Metis issues and snapping hundreds of photos which are currently up in Calgary’s Glenbow Museum. Amber tells me that one of her favourite Brady pictures is from the 1920s of two Indigenous women dancing at a hall.

It is important to look at pictures like the ones that Brady has taken because there is a lot that most people don’t “know about these women’s lives,” she says.

“I agree,” I say, “a lot of the time it seems that people’s knowledge of Indigenous women both in the past and present is often restricted to the stereotypes that the media uses”.

In contrast, Brady’s work enables us to view them as the real, multidimensional individuals they were/are.

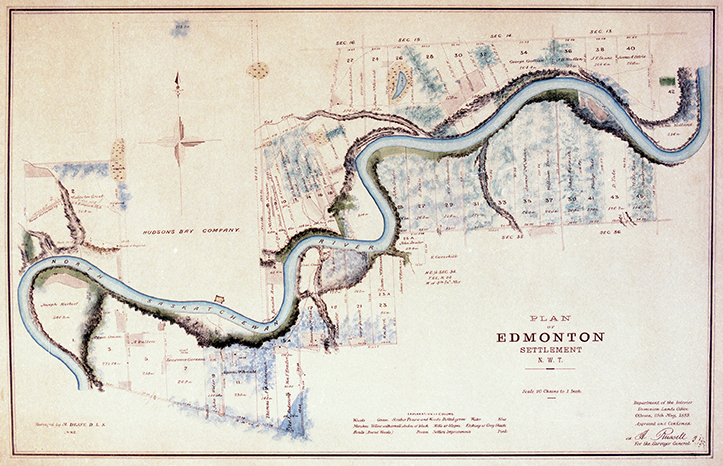

Next, we discussed Alberta’s rich Metis history. Amber told me that historically, the Metis people built their settlements on river lots. The Metis did this because they wanted to be able to plant a variety of “crops for the spring and then [be able to] go on the buffalo hunt” in the summer. Being near water, by setting up river lots, gave them the means to do this.

Amber tells me “that when you line [the river lots] up with a map of [Alberta or Edmonton] today, there [are] certain key places where roads [also] are today” . On their website, the City Museum of Edmonton elaborates by saying that, “the shape of these lots influenced the form of our city’s urban landscape, and the names of one-time owners – Fraser, Garneau, Groat – provide appellations for neighborhoods, roads, and other Edmonton landmarks.” River lots provide a prime example of how Edmontonians continue to be connected to Metis peoples and their history, today.

Image courtesy of the City of Edmonton Archives EAM-85.

“Metis history is everywhere,” you just need to know where to look, she says smiling.

That being said, the Metis were not the only nation that lived on the river lots. The Papachase Cree and the Iroquois also inhabited these spaces. In 1692, the three bands formed the Iron Confederacy which gave them the chance to intermix. Unfortunately, this alliance did not last long. The reservation period of 1851-1880 separated Indigenous people based on what band their ancestors were in.

Amber critiques this period for the huge identity discord that it created, and for the negative effects that it left on Indigenous people. She notes that not many ordinary people know this history and neither do many academics. This, for me, underscores the importance of Amber’s work towards preserving and educating others about Alberta’s rich Indigenous histories.

We finished our interview by talking about the fur trade.

“In school, I had always been taught history from the perspective of a white teacher. So, I am curious what your thoughts are about the fur trade from an Indigenous lens,” I asked.

Trade was an important part of Indigenous culture and ceremony. “It [was] something you [had] to [have] a relation with” and was very much operated as a family business, Amber says. European settlers often relied on Indigenous women to help them understand the trade rules. Additionally, Amber notes, 75% of traded goods were women-made goods and textiles.

Amber is extremely happy to have been appointed to the position of Historian Laureate. In the past, Edmonton’s historian laureates have all come from white backgrounds. And while she believes that it is valuable to preserve these histories, it is important to her that we begin to think about adding Indigenous histories to the archives too, since they also played a central part in where Edmonton is today. Amber hopes that through her work as the HL, she and the “300 people behind [her]” can play a role in restructuring history so that Indigenous and non-Indigenous Edmontonians are made more aware of the relations they share in the present. “History creates the context for our current world,” she says, and “I strive to connect Edmontonians to that history.”

If you are interested in learning more about Amber and seeing her work as the Historian Laureate, Amber encourages people to follow her via the Historian Laureate Facebook page: https://m.facebook.com/yeghistory/, as well as, on instagram @a.munet and @avioletart.