The Last Letter Home

Review and photographs by Mariah Hess

Every year on November 11th, I reflect on a time in history that I was not yet alive for. It has been 101 years since the First World War came to an end, and although I did not experience it first hand, I am reminded to remember the atrocities, the sacrifices, and the freedom that came to be.

‘Remembering the First World War’ is a temporary exhibit in the Human History Hall at the Royal Alberta Museum that runs until October 17, 2020. It features objects from the museum’s Military and Political History collection to commemorate 100 years since the war. These objects “act as tangible representations of an intangible thing – memory,” and it is through exhibits like this that we continue to be reminded of our history.

There is a sense of duty that overcomes me every time I visit a war exhibit. Objects, mementos, and images implicitly tell me to bow my head in reverence for the past.

I fully expected to experience this sense of duty during my visit, but I was hoping that this exhibit would shine light on a new perspective for me. I’ve learned about the war under various circumstances throughout my life, and I was searching for an unforgettable impression.

The first thing to catch my eye as I entered the exhibit was a war cannon painted in camouflage colours, perched dutifully in the centre of the room under a spotlight. This stood out in stark contrast to the rest of the dimly lit room.

Glass cases were situated around the room, seemingly in no particular order. I decided to make my way around the exhibit in a clockwise direction. The first case was entitled ‘Stanley’s letter to Hazel, November 11, 1918.’ The letter on display revealed the relief of Stanley, a soldier, that the war was now over.

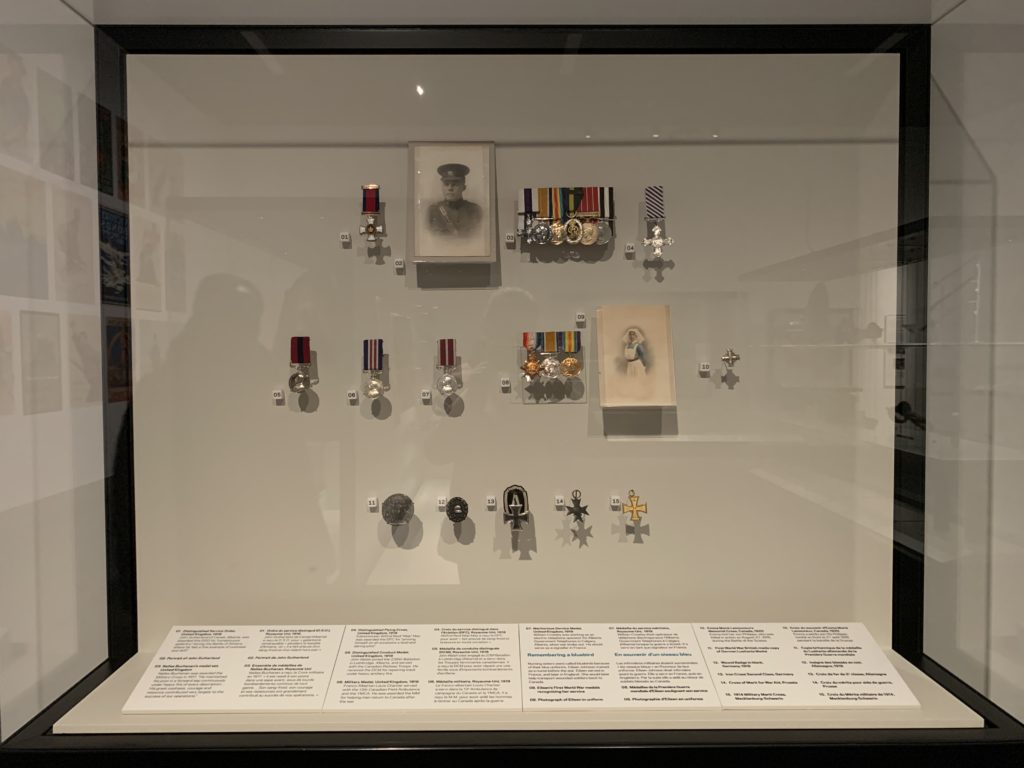

As I continued around the room, I was unsurprised by what I saw – machine guns, rifles, handguns, and knives. On the far-left wall were colourful posters that advertised victory bonds. Shiny medallions were on display, such as the Distinguished Flying Cross, a Military Medal, and a Meritorious Service Medal.

I appreciated the connection that the exhibit made between the tangible and the intangible, the connection between physical objects and memory. Some of the items were actually recovered from the war, and some were replicas. It forced me to view these objects with a particular purpose: to understand that these were all part of our history.

With this purpose in mind, I felt guilty for being slightly indifferent to what I was seeing. It felt as though I was wandering aimlessly through this exhibit. Nothing was sticking out to me. I’ve seen all of these objects many times before.

And then it hit me. A letter. A personal testament. It drove home a human connection between me in the present, and those that have gone before me in the past. I snapped out of my purposeless wandering as my heart began to swell with sorrow and pain.

Dear Mother, This is just a line or so to tell you that I am still O.K. but very dirty and verminous.

You may be pleased to hear that I have been awarded the Military Cross. Your son is therefore a hero in a modest sort of way, at least to outsiders.

By the time I shall write again I hope that we shall be clear of this rotten place.

With love, Allen

This was his last letter home.

In further research, I found that Lieutenant Allen Oliver was born on March 15, 1893 in Edmonton. He was a former member of The Royal Ottawa Golf Club. While these points are not necessarily interesting, they are important because they show that Oliver was just like you and me. He was human. I re-read his letter to his mother a couple of times. Oliver didn’t seem to be writing in a tone of urgency. It seemed as though he was taking his circumstances day by day, with the hope that one day he’d be able to write good news to his mother. The fact that he never lived to have this opportunity brought me pain.

In the midst of a battle that took the lives of 16 million, it is easy to focus on numbers and ignore the human element of each individual. They were not merely soldiers; they were people who held meaningful identities and stories.

Oliver’s letter halted my indifference towards the exhibit. I thought about how it must have felt to be a mother or a child in these unpredictable circumstances. Neither Allen nor his mother could have known when their last exchange would be, for death usually appears unannounced. This is a scary reality that humbles me.

Although the exhibit did not leave me with any new life-altering perspective, I still left with a heart full of humility. It was only 101 years ago that young men and women sacrificed their lives for the world. It could have been you; it could have been me. For that, it is important to remember these heroes and find gratitude – not only for what they did in the past, but what they did for our present and future.

Remembering the First World War continues at the Royal Alberta Museum until October 17, 2020

9810 103a Avenue, Edmonton

website